Part 4: Refs and branches

At the end of part 3, we’ve seen how to take snapshots of the repo with trees, attach context with commits, and construct commits into a sequence – but passing around commit hashes is unwieldy. In this final part, let’s see how we can give commits friendlier names.

Creating our first branch

So far we’ve worked exclusively in the .git/objects folder. What about .git/refs?

If we look, we see it just contains two empty directories:

$ ls .git/refs

heads tags

$ find .git/refs -type f

We can use the update-ref command to create a named reference to a commit. Like so:

$ git update-ref refs/heads/master fd9274dbef2276ba8dc501be85a48fbfe6fc3e31

If you have another look inside .git/refs, you’ll see a new file has been created:

$ find .git/refs -type f

.git/refs/heads/master

$ cat .git/refs/heads/master

fd9274dbef2276ba8dc501be85a48fbfe6fc3e31

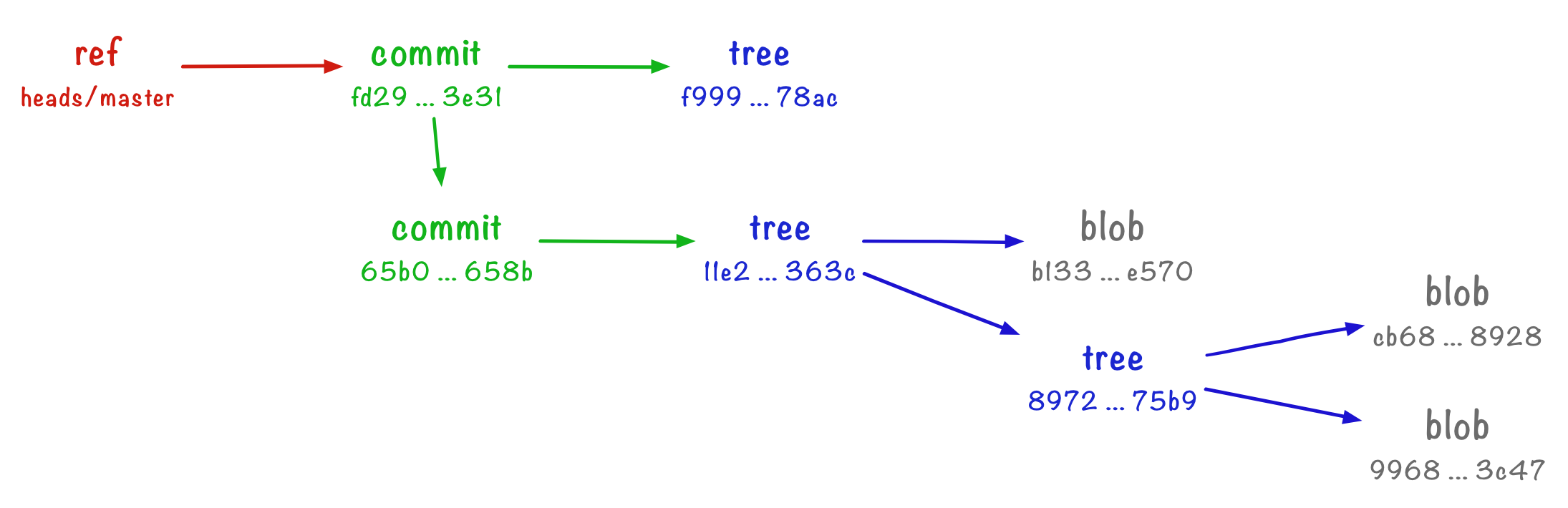

The reference master is a pointer to the commit fd9...e31. Anywhere we might use the commit ID, we can use master as a more convenient shortcut. This is what it looks like:

Let’s use the ref in an example:

$ git cat-file -p master

tree f999222f82d1ffe7233a8d86d72f27d5b92478ac

parent 65b080f1fe43e6e39b72dd79bda4953f7213658b

author Alex Chan <alex@alexwlchan.net> 1520806875 +0000

committer Alex Chan <alex@alexwlchan.net> 1520806875 +0000

Adding c_creatures.txt

We can check the value of a ref with the rev-parse command:

$ git rev-parse master

fd9274dbef2276ba8dc501be85a48fbfe6fc3e31

A ref in the heads folder is more commonly called a branch. So with this command, we’ve created our first Git branch!

Adding commits to a branch

Now let’s create another commit, and see what happens to our branch. Notice that I can pass the parent commit with our named ref:

$ echo "Flying foxes feel fantastic but frightening" > foxes.txt

$ git update-index --add foxes.txt

$ git write-tree

c08523d153f6415cda07ea27948830407f243a37

$ echo "Add foxes.txt" | git commit-tree c08523d153f6415cda07ea27948830407f243a37 -p master

b023d92829d5d076dc31de5cca92cf0bd5ae8f8e

So we have a new commit, and we can see it if we run git log:

$ git log --oneline b023d92829d5d076dc31de5cca92cf0bd5ae8f8e

b023d92 Add foxes.txt

fd9274d Adding c_creatures.txt

65b080f initial commit

But has this commit been added to our master branch? Let’s have a look:

$ git log --oneline master

fd9274d Adding c_creatures.txt

65b080f initial commit

No!

Unlike in the world of porcelain commands, branches/refs aren’t automatically advanced to point at new commits. If we create new commits, we need to update the ref manually. Like so:

$ git update-ref refs/heads/master b023d92829d5d076dc31de5cca92cf0bd5ae8f8e

$ git log --oneline master

b023d92 Add foxes.txt

fd9274d Adding c_creatures.txt

65b080f initial commit

Working with multiple branches

Let’s create a second branch in our repository:

$ git update-ref refs/heads/dev 65b080f1fe43e6e39b72dd79bda4953f7213658b

Now dev is a reference to the initial commit in the repository. We can see the list of references we’ve created either by inspecting the filesystem, or by using a porcelain branch:

$ find .git/refs -type f

.git/refs/heads/dev

.git/refs/heads/master

$ git branch

dev

* master

Notice that there’s a * next to the name of the master branch – this is the current branch, and if we used porcelain commands, it’s the branch where new commits would be added.

The current branch is determined by the contents of the HEAD file:

$ cat .git/HEAD

ref: refs/heads/master

We can use symbolic-ref to tell Git we’re on the dev branch instead:

$ git symbolic-ref HEAD refs/heads/dev

$ git branch

* dev

master

Here HEAD is a reference that has a special meaning. We can use it as a shortcut for commit hashes just as we did with our manually created references above. For example:

$ git cat-file -p HEAD

tree 11e2f923d36175b185cfa9dcc34ea068dc2a363c

author Alex Chan <alex@alexwlchan.net> 1520806168 +0000

committer Alex Chan <alex@alexwlchan.net> 1520806168 +0000

initial commit

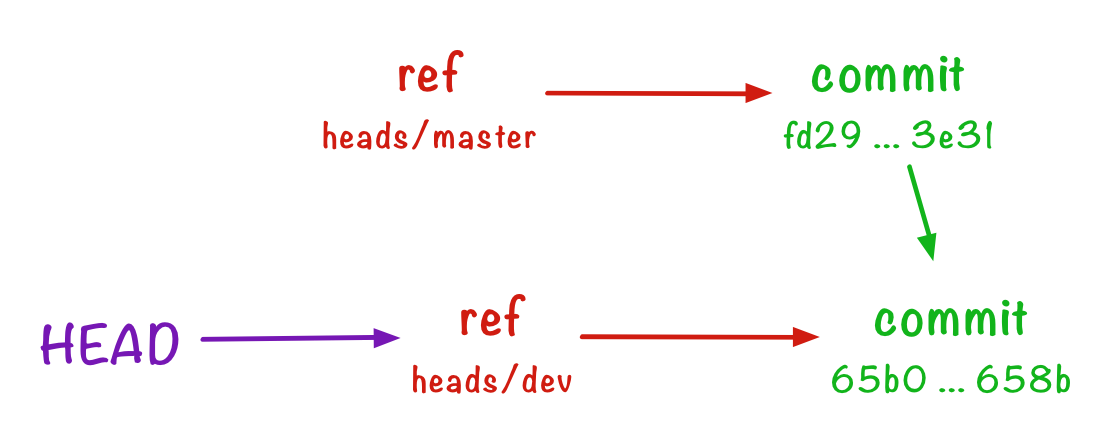

Here’s a quick diagram that summarises what we’ve learnt: refs point to commits (and you could create two refs that point to the same commit). HEAD is a special reference that points to another ref.

Let’s wrap up with a final set of exercises.

Exercises

- Look in your

.git/refsdirectory. Check it only contains two empty directories. - Take one of the commits you created in part 3, and create a master branch. Use a porcelain

git logto look at all the commits on this branch. - Have another look inside the

.git/refsfolder. What do you see? - Create some more commits, and then check that master hasn’t changed. Advance master to your latest commit.

- Create a second branch dev. Add some more commits, and advance dev to your latest commit. Check that master hasn’t moved.

Repeat this a couple of times, so you get really comfortable creating branches. Use a git branch to check your work.

To finish off, here are a couple of bonus exercises:

- If a branch is created by a file in

.git/refs, can you think how you might delete a branch? Try it, and usegit branchto check you were successful. - There's a second folder in

.git/refs--tags. What if you create a ref that points to someting in that folder? What porcelain command can you use for a list of refs in this folder?

Useful commands

git update-ref refs/heads/<branch> <commit ID>> git rev-parse <branch> git log <branch> git branch git symbolic-ref HEAD refs/heads/<branch> Notes

Exercises 1–5 are repeating the steps in the theory section above.

In exercise 6, you can delete a branch by deleting the file in the refs folder. That’s all a branch is – a pointer file.

$ rm .git/refs/heads/master

$ git branch

* dev

In exercise 7, the tags folder is used to store Git tags – lightweight pointers to specific commits in the history. These are often used to indicate versioned releases, and generally don’t move with new commits. Here’s a short example:

$ git update-ref refs/tags/v0.1 dev

$ find .git/refs/tags -type f

.git/refs/tags/v0.1

$ git tag

v0.1

$ git rev-parse tags/v0.1

65b080f1fe43e6e39b72dd79bda4953f7213658b

This is why people sometimes say “branches are cheap” in Git – they’re just tiny pointers to commits, which take up almost no disk space.

This is the final part of the workshop. There’s a short recap and conclusion which reviews everything you’ve learnt.