Part 2: Blobs and trees

I’m assuming you’ve already read and completed part 1, which explains how to store and retrieve single files. If not, go back and do that first.

At the end of part 1, we saw that Git could store the contents of a single file – but it didn’t save anything about filenames. In this part, we’ll see how to save filenames and directory layout.

Adding files to the index

In Git, the index or staging area is a temporary snapshot of your repository. It’s a collection of files that have been modified, but not yet saved to the permanent history. In a porcelain Git workflow, you add files to the index with git add, then take a snapshot of the index with git commit. With plumbing, there are several extra steps.

We can save a file to the index with the update-index command:

$ git update-index --add animals.txt

Note that if you haven’t saved a file already with hash-object, it’s done automatically for you.

If we look in the .git directory, there’s a new file index:

$ ls .git

HEAD description index objects

config hooks info refs

We can see what we’ve added to the index with the plumbing command ls-files:

$ git ls-files

animals.txt

Alternatively, the porcelain command status gives a more verbose view of the index:

$ git status

On branch master

No commits yet

Changes to be committed:

(use "git rm --cached <file>..." to unstage)

new file: animals.txt

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

alliteration.txt

c_creatures.txt

sea_creatures.txt

But the index is only temporary. We can add or delete files, and when the index changes, the previous state is lost. How can we save this snapshot permanently?

Taking a permanent copy of the index

To take permanent copies of the snapshot, we need another plumbing command: write-tree:

$ git write-tree

dc6b8ea09fb7573a335c5fb953b49b85bb6ca985

We’ve got back a hash – this is another Git object!

$ find .git/objects -type f

.git/objects/a3/7f3f668f09c61b7c12e857328f587c311e5d1d

.git/objects/b1/3311e04762c322493e8562e6ce145a899ce570

.git/objects/ce/289881a996b911f167be82c87cbfa5c6560653

.git/objects/dc/6b8ea09fb7573a335c5fb953b49b85bb6ca985

Let’s inspect it with cat-file:

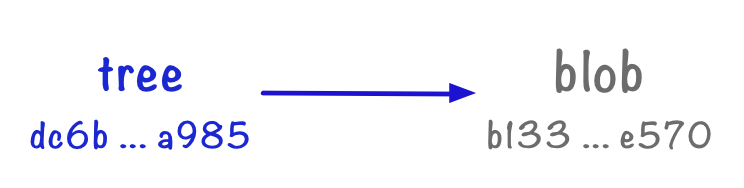

$ git cat-file -p dc6b8ea09fb7573a335c5fb953b49b85bb6ca985

100644 blob b13311e04762c322493e8562e6ce145a899ce570 animals.txt

This looks quite different to the other objects we’ve seen so far. A tree is a list of pointers to other objects – one object per row. There are four parts to the row:

100644is the file permissions. Git only distinguishes between 644 (non-executable) and 755 (executable).blobis the type of the object (more on that below).b13...570is the ID of the file contents we saved in part 1.animals.txtis the name of that file.

This is enough to completely reconstruct this file: we know what it should be called, what the contents should be, and whether to make it executable.

And what sort of object is this? We can call cat-file with “-t” for “type” to find out, like so:

$ git cat-file -t a37f3f668f09c61b7c12e857328f587c311e5d1d

blob

$ git cat-file -t dc6b8ea09fb7573a335c5fb953b49b85bb6ca985

tree

A blob object stores the contents of a file, but doesn’t know what the file is called. Those are what we created in part 1. Now we’re creating tree objects, which know what files are called. A tree can point to a blob to describe the file contents.

Subdirectories

What if we create a more complex directory structure? Let’s put a subdirectory inside our repo, and store some files there:

$ mkdir underwater

$ echo "Dancing dolphins delight in the Danube" > underwater/d.txt

$ echo "Electric eels exude exuberance and elegance" > underwater/e.txt

Add them to the index:

$ git update-index --add underwater/d.txt

$ git update-index --add underwater/e.txt

And create a tree:

$ git write-tree

11e2f923d36175b185cfa9dcc34ea068dc2a363c

Now let’s inspect our new tree:

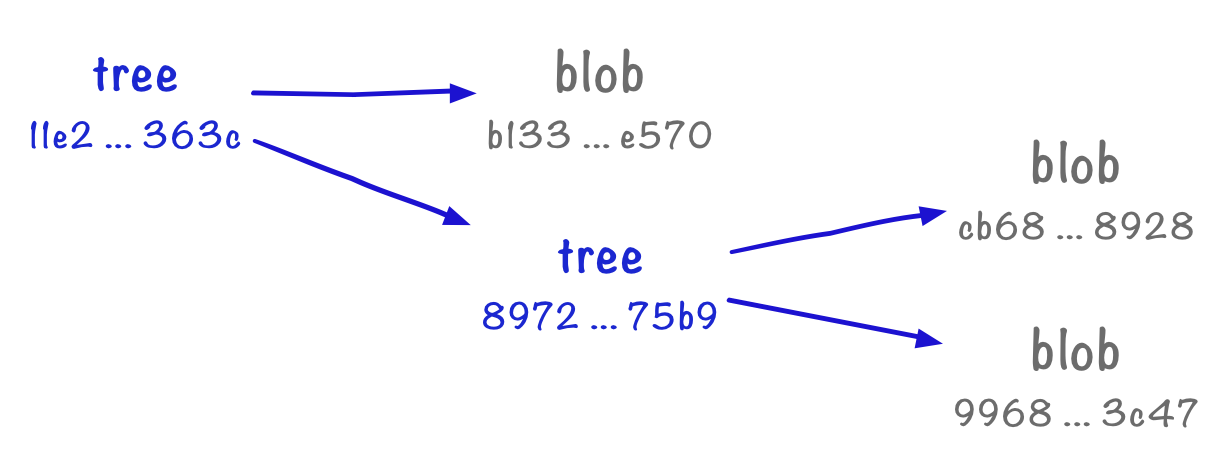

$ git cat-file -p 11e2f923d36175b185cfa9dcc34ea068dc2a363c

100644 blob b13311e04762c322493e8562e6ce145a899ce570 animals.txt

040000 tree 8972388aa2e995eb4fa0247ccc4e69144f7175b9 underwater

Now our tree has two lines: the first is the blob we’d already saved, and the second line is a reference to another tree object. It follows the same format as the first: the type of the object, a pointer to another Git object, and its name in the filesystem. Here, it’s telling us there’s a tree 897...5b9 which represents the directory underwater.

If we inspect that tree object in turn, we see the two files in that directory:

$ git cat-file -p 8972388aa2e995eb4fa0247ccc4e69144f7175b9

100644 blob cb68066907dd99eb75642bdbd449e1647cc78928 d.txt

100644 blob 9968b7362a7c97e237c74276d65b68ca20e03c47 e.txt

Trees and blobs are analogous to the structure of the filesystem – blobs are like files, trees are like directories. A tree can point to blobs or other trees, which correspond to subdirectories.

Here’s a diagram to show our current repo:

Now let’s put these new concepts into practice!

Exercises

- Take a file you created in part 1, and add it to the index.

- Check that you can see an

indexfile in your.gitdirectory. - Use a plumbing command to check that you’ve added it to the index. Then use a porcelain

git statusto double-check the result. - Create a tree from the current index.

- Look in

.git/objects. Can you see the tree you just created? - Use a Git plumbing command to inspect the tree. Make sure you understand what it means.

Create some new files, and add them to your tree as well, repeating steps 1–6. Make sure you’re comfortable creating trees.

- Now make an edit to an existing file, and add the new version of that file to a tree. Use a plumbing command to inspect the tree.

- Create a subdirectory of your main directory, and create some files inside that folder. Add those files to a tree, and inspect the contents of that tree as well. Make sure you understand the trees you've created.

Useful commands

find .git/objects -type f .git/objects git cat-file -p <object ID> git cat-file -t <object ID> git update-index --add <path> git ls-files git write-tree Notes

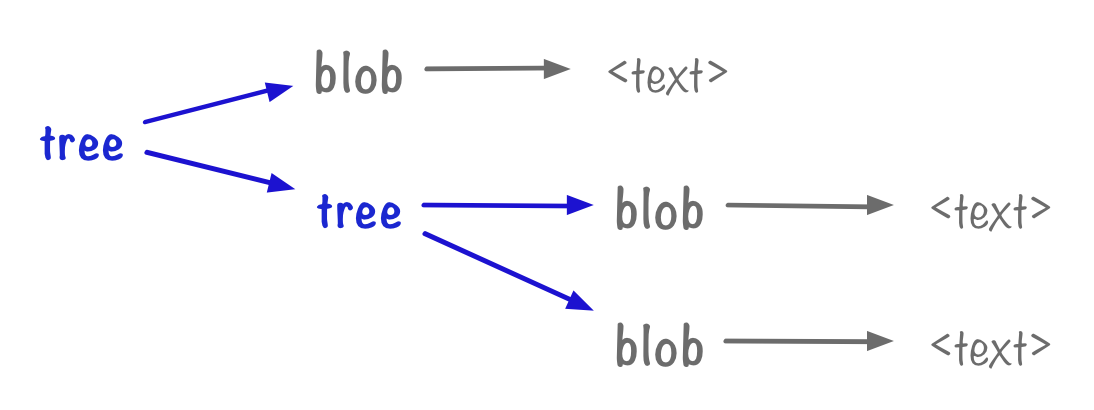

Let’s recap: blobs are objects that point to the contents of a file. Trees are objects that point to blobs or other trees, and give names to the objects they point to.

Here’s a diagram:

At this point, we have enough to take a complete snapshot of a repository.

If we start at a tree, we can rebuild everything it points to. For every blob it points to, we can unpack the contents of the blob into a named file. For every tree it points to, we can create a subdirectory and repeat the process inside the subdirectory. If we do this repeatedly, we’ll eventually get a copy of everything saved in the original tree.

So now we have snapshots, but we don’t have any context. What makes a particular tree special? Why is this tree an interesting point in the history of the repository? For that, we need to look at commits. Let’s move on to part 3.