Part 1: The Git object store

We’ll start by working with single files.

When I run this workshop in person, I start with a short demo on the command line. This introduces the new material, and I explain what I’m doing as I go along. Then we break into small groups, and everyone goes through some exercises to try what I’ve just shown. After everyone’s done, we come back together and have a discussion about what we’ve just seen.

Here, I’ve included the commands and output from my demo, and interspersed my explanations with the commands. You should read the theory, and make sure you understand it – then try working through the exercises yourself.

At the end of part 1, you should be able to store and retrieve individual files from Git.

Initialising a new Git repo

Let’s start by creating an empty directory:

$ mkdir plumbing-repo

$ cd plumbing-repo

Then we can create a new Git repository with the git-init command:

$ git init

Initialized empty Git repository in ~/plumbing-repo/.git/

This command creates the .git directory, which is where Git stores all of its information. If you delete everything except .git, you can still rebuild your entire repository – as we’ll see in the rest of the workshop.

The command also creates a few other empty directories for us. If you’ve never looked inside the .git directory before, let’s start now:

$ ls .git

HEAD description info refs

config hooks objects

Here’s what we have:

-

The

HEADfile tells Git which branch we’re working on – we’ll skip it for now, and come back to it in part 4 “refs and branches”. -

The

configfile contains repo-specific configuration. We’re not using it in this workshop. -

The

descriptionfile is only used by the GitWeb program – it can be ignored. -

The

hooksdirectory is used to store scripts that fire on certain events – for example, running a linter before you commit. We don’t cover it in this workshop, but it can be very useful! See the Git docs for more information. -

The

infodirectory has a single file,exclude, which contains a list of per-repo ignores. Like a gitignore file, but it doesn’t need to be checked in. We won’t use it in this workshop. -

The

objectsdirectory should be empty (aside from two more empty directories) – but we’re about to see what it holds. -

The

refsdirectory is also empty – we’ll see it again in part 4.

So now we have an empty repository, and we’ve had a look inside the .git directory – let’s write our first files!

Storing individual files with “hash-object”

Here we create our first file, then save it to the Git object store:

$ echo "An awesome aardvark admires the Alps" > animals.txt

$ git hash-object -w animals.txt

a37f3f668f09c61b7c12e857328f587c311e5d1d

This is our first example of a plumbing command. The hash-object command takes a path to a file, reads its contents, and saves the contents of the file to the Git object store. It returns a hex string – the ID of the object it’s just created.

If we look in .git/objects, we can see something with the same name:

$ find .git/objects -type f

.git/objects/a3/7f3f668f09c61b7c12e857328f587c311e5d1d

We’ve created our first object! This object is a binary file that holds the text we just saved.

You’ll see the first two characters are a directory name. A typical repo has thousands of objects, so Git breaks up objects into subdirectories to avoid any one directory becoming too large.

The object ID is chosen based on the contents of the object – specifically, prepend a short header to our file, then take the SHA1 hash. This is how Git stores all of its objects – the content of an object determines its ID. The technical name for this is a content-addressable filesystem.

This means that if we try to save the file a second time, because the contents are the same, nothing changes:

$ git hash-object -w animals.txt

a37f3f668f09c61b7c12e857328f587c311e5d1d

$ find .git/objects -type f

.git/objects/a3/7f3f668f09c61b7c12e857328f587c311e5d1d

We have the same set of objects as before.

Retrieving objects with “cat-file”

Now we’ve saved an object, we can use a second plumbing command to retrieve it:

$ git cat-file -p a37f3f668f09c61b7c12e857328f587c311e5d1d

An awesome aardvark admires the Alps

The cat-file command is used to inspect objects stored in Git. The “-p” flag means “pretty” – it pretty-prints the contents of the object. We’ll be using this command a lot!

With this command, we can restore our file even if we delete it – because the object is kept safe in the .git directory:

$ rm animals.txt

$ git cat-file -p a37f3f668f09c61b7c12e857328f587c311e5d1d > animals.txt

$ cat animals.txt

An awesome aardvark admires the Alps

Exercises

These are some exercises to get you used to the idea of storing and retrieving files from the Git object store:

- Create a new directory, and initialise Git.

- Look inside the

.gitfolder. Make sure you understand what it contains. - Using a text editor, create a file and write some text.

- Use a Git plumbing command to save the contents of your file to the Git object store. Check you can see the new object in

.git/objects. - Use a Git plumbing command to inspect the object in the database.

Repeat exercises 3–5 a couple of times.

- Make an edit to your file, then save the new version to the Git object store. What do you see in

.git/objects? Before you look: what do you expect to see? - Delete a file, then recreate it from the Git object store.

- What if you save two files with the same contents, but different filenames? What do you see in

.git/objects? What do you expect to see?

Useful commands

mkdir <path> git init ls .git .git directory find .git/objects -type f .git/objects git hash-object -w <path> git cat-file -p <object ID> Notes

A brief recap of the exercises: steps 1–5 are repeating what I did in the demo.

In exercise 6, you see that Git creates an entirely new object when you edit a file – and there’s nothing to indicate the two files are related.

$ echo "Big blue basilisks bawl in the basement" > animals.txt

$ git hash-object -w animals.txt

b13311e04762c322493e8562e6ce145a899ce570

$ find .git/objects -type f

.git/objects/a3/7f3f668f09c61b7c12e857328f587c311e5d1d

.git/objects/b1/3311e04762c322493e8562e6ce145a899ce570

For exercise 7, if you delete a file, you can restore it using shell redirection:

$ rm animals.txt

$ git cat-file -p b13311e04762c322493e8562e6ce145a899ce570 > animals.txt

But notice that you can restore an object to a file with a different name to the original:

$ git cat-file -p b13311e04762c322493e8562e6ce145a899ce570 > alliteration.txt

And in exercise 8, if you save two files with the same contents, they both get the same ID. Given that IDs are based on the contents of the file, it follows that identical contents mean identical IDs.

$ echo "Clueless cuttlefish crowd the curious crab" > c_creatures.txt

$ cp c_creatures.txt sea_creatures.txt

$ git hash-object -w c_creatures.txt

ce289881a996b911f167be82c87cbfa5c6560653

$ git hash-object -w sea_creatures.txt

ce289881a996b911f167be82c87cbfa5c6560653

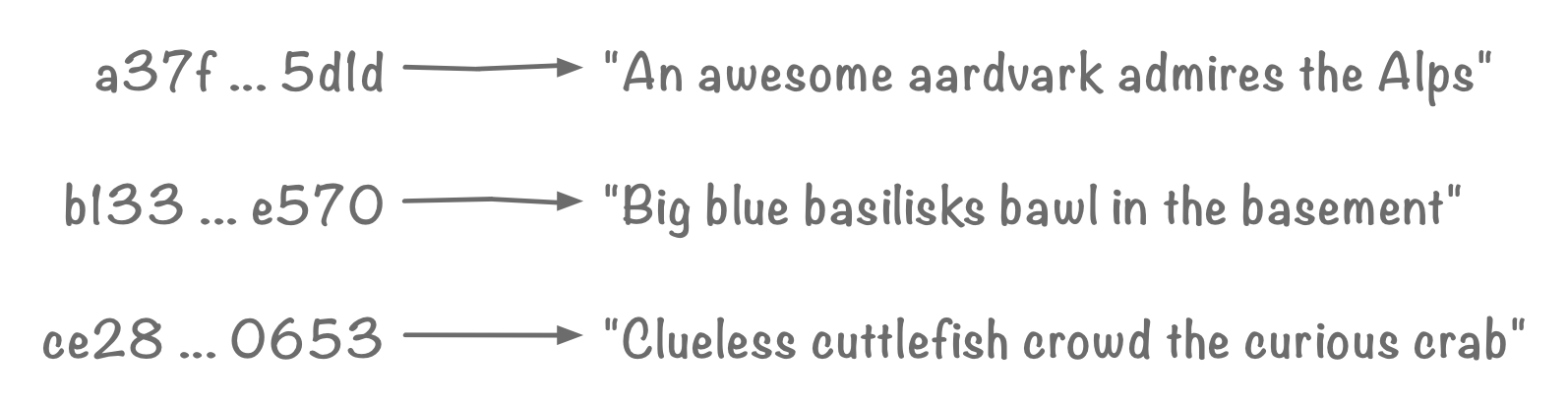

Hopefully you see is that Git is only saving the contents of our files – it isn’t saving anything about their filenames. Each object ID is a pointer to some text, but that text isn’t associated with a filename. Here’s a diagram showing the three objects we have so far:

If we want to use Git to save more than a single file, we need to know what our files are called! In part 2, we’ll see how we can use trees to save the filenames and directory structure of our repository.