Monki Gras 2019: The Curb Cut Effect

Earlier today I did a talk at Monki Gras 2019. The theme of the conference is “Accessible Craft: Creating great experiences for everyone”, so I did a talk about inclusive design – and in particular, something called the Curb Cut Effect.

I originally pitched a talk based on Assume Worst Intent, because if you’re thinking about inclusion you might think about ways to avoid exclusion (specifically, exclusion of harassment and abuse victims). That talk was definitely too narrow for this conference, but James isolated a key idea – making a service better for vulnerable uses makes it better for everyone – and I wrote an entirely new talk around it.

The talk went really well – everybody was very nice afterwards, and I’m enjoying the rest of talks too. (Notes on those will be a separate post.) It was a lot of fun to write and present.

The talk was recorded, and you can watch it on YouTube:

You can read the slides and my notes on this page, or download the slides as a PDF.

Links/recommended reading

-

Mismatch, by Kat Holmes, was a useful book. It’s a short but detailed book that I’d recommend for anybody wanting to learn more about inclusive design. The penultimate chapter was especially helpful for finding a good framing.

-

Some general articles about the Curb Cut Effect that I found useful:

- The Curb Cut Effect: How Making Public Spaces Accessible to People With Disabilities Helps Everyone, which goes into additional detail about how designs go from “assistive technology” to “ubiquitous”.

- The Curb-Cut Effect, by Angela Glover Blackwell.

- The Curb Cut Effect, or Why It Is Basically Impossible To Appropriate From Disabled People

-

If you want to read more detail about Jack Fisher’s work to install curb cuts in Kalamazoo, MI:

- Smashing barriers to access: Disability activism and curb cuts from the Smithsonian

- The Curb Ramps of Kalamazoo: Discovering Our Unrecorded History from the Independent Living Institute

- Creating Curb Cuts in Encore Magazine

-

Electronic Curb Cuts, by Steve Jacobs, is a long list of other examples of the curb cut effect. I drew a couple of examples from here (the typewriter and OCR), and there are plenty of others I didn’t have time to mention.

Slides and notes

Hi, I’m Alex. I’m going to talk about the Curb Cut Effect, what it is, and how we might use it.

The Wellcome Collection building lit up in purple to mark International Day of Persons with Disabilities in December 2018. Image credit: Wellcome Collection.

I’m a software developer at Wellcome Collection, a free museum and library on Euston Road.

At Wellcome, we’ve been thinking a lot about architecture recently. Our current exhibition, Living with Buildings, is all about the effect of architecture on human health, so I wanted to start today by telling you all the story of architecture – specifically, the story of a common architectural feature that we all walk past every day without a second glance.

A dropped kerb around the back of UCL, near the Wellcome offices. Image credit: me!

I’m talking about those areas where the kerb dips to form a ramp – giving a level, step-free path from the road to the pavement. In the UK, these are usually accompanied by a textured yellow surface (pictured).

They go by several names – in the UK we call them dropped kerbs, in the US they’re called curb cuts (one of the few American spellings that adds the letter U), and they have other names around the world. The American spelling is mostly common, and that’s what I’ll use for the rest of the talk, but you can mentally substitute “curb cut” for your preferred term.

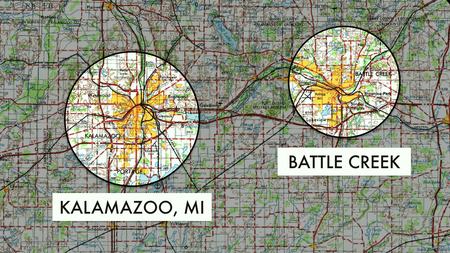

A map showing part of Michigan, highlighting Kalamazoo and Battle Creek. Image credit: original map from the US Geological Survey.

One of the earliest examples of curb cuts was in Kalamazoo, MI. (Great name!)

There was a man called Jack Fisher, born in Kalamazoo in 1918. Like many young men of his age, he enlisted in the Army during the Second World War.

He was involved in a jeep accident in 1943. While he was recovering in hospital, he read the records of other patients with similar injuries to keep himself occupied. (Because 1940s privacy laws.)

He returned to Kalamazoo with steel braces from his hip to his neck, and a heavy limp. After the war, he graduated from Harvard law school (very impressive), but none of the established firms would take him – he was a disabled veteran, who might trip and injure himself, and need compensation. So they chose not to hire him. (Because 1940s labour rights.)

So he worked as an attorney in his own practice. He became well-known among other disabled veterans in and near Kalamazoo – of which there were many, because there was a nearby hospital at Battle Creek which specialised in amputee treatment and rehabilitation.

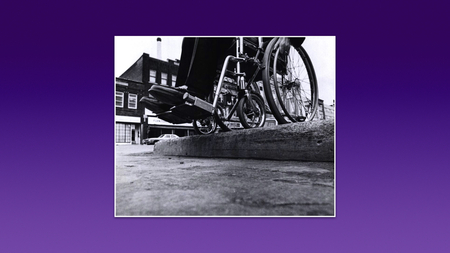

A wheelchair standing at an raised, inaccessible curb. Image from an article by the Smithsonian.

Working closely with them, he became aware of the problems and challenges they faced.

One of those problems: Kalamazoo had tall curbs (up to 6 inches). This was a problem – people would trip, injure themselves, damage prosthetic limbs, and for wheelchair users they’re a total nightmare. Tall kerbs are inaccessible, and prevent people getting around, socialising, working and so on.

A ramp with hand rails on the streets of Kalamazoo. Image from an article in Encore Magazine.

So in 1945, Jack Fisher took it upon himself to fix this, and petitioned the city commission for curb cuts and hand-rails. Ditching the step would make it easier for people to get around. The city authorised their construction and ran a small pilot program, they were very successful, and they grew in number.

Kalamazoo is one of the earliest examples of dropped kerbs, but the same story plays out in lots of other places – curb cuts were installed in lots of places to make the streets more accessible for disabled people and wheelchair users.

So curb cuts make the roads more accessible for wheelchair users and disabled people. Yay!

But they’re not the only people to benefit, so do:

- Parents with prams

- Workers pulling heavy carts

- Travellers with wheeled suitcases

- Runners

- Cyclists

- Skateboarders!

And probably others.

Wcould call this a “force multipler” or a “happy accident”, but really this is the original example of the “Curb Cut Effect”.

The Curb Cut Effect comes in many forms, but the way I think of it is:

Making something better for disabled people can make it better for everyone.

What this means for us, as people who build things:

Designs that think about disabled people are better designs for everyone

And we reflect this is the words we use: it’s why we don’t talk about handicapped design or barrier-free design. We talk universal design. We talk about good design.

(Repeat the Curb Cut Effect.)

Let’s look at a few examples.

One of the earliest examplse predates Kalamazoo by more than a century.

This is the Countess Carolina Fantoni da Fivizzano. She lived in the early nineteenth century, and was the friend and lover of the Italian inventor Pellegrino Turri.

They’d write each other letters, but she lost her sight as an adult, and was unable to write herself. That meant the only way to send letters was to dictate to somebody else – but she wanted to send letters in private. Together they built a machine that let her write letters by pressing a key for each letter – allowing her to “type” letters.

Writing with type… a type-writer, of sorts.

This was one of the earliest iterations of the typewriter. It made writing accessible to the blind, and the derivatives became the modern-day keyboard. A machine created to help one blind woman write love letters was the basis for a fundamental input device for modern computing.

Somebody using an email client on a laptop. Image credit: rawpixel.com on Pexels.

Speaking of love letters… let’s talk about email!

(You don’t use email to write love letters? Sounds fake.)

Email has become a ubiquitous part of modern comms, but where did it come from? Why was it invented?

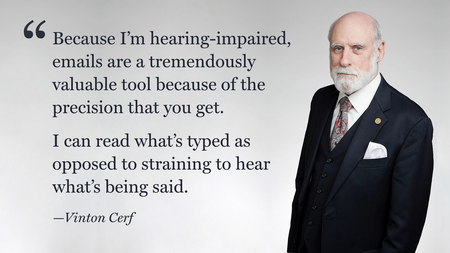

A picture of Vinton Cerf, taken from his Royal Society photo and overlaid with a quote from a CNET article.

This is Vinton Cerf. He’s often called the “Father of the Internet”, did a lot of work on the early Internet (then-ARPANET) protocols, is a strong advocate for accessibility, and led the work on the first commercial email program.

Why?

Because he’s hard-of-hearing, and his wife Sigrid is deaf. His work on email started, in part, as a way for them to stay connected when they weren’t in the same room. At the time, the alternative was the telephone, which was a bit of a non-starter.

Here’s a quote he gave to CNET that sums it up nicely:

Because I’m hearing-impaired, emails are a tremendously valuable tool because of the precision that you get.

I can read what’s typed as opposed to straining to hear what’s being said.

Email started as a key technology for people who are deaf or have hearing loss – or who are just separated by time and space.

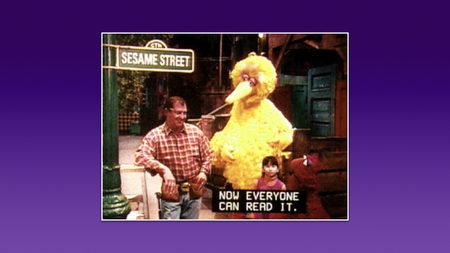

Sticking with hearing loss, let’s talk about captions.

It was originally intended to help deaf people understand movies with dialogue or sound effects. Closed captions were first broadcast in the 1970s. They were expensive, needed specialist equipment, and most content wasn’t captioned – today things are generally better. And indeed, they help people who are deaf or hard-of-hearing, but lots of other people besides:

- MAYBE YOU’RE IN A NOISY ENVIRONMENT, LIKE A BAR OR GYM, AND YOU CAN’T HEAR THE TELEVISON OVER THE BACKGROUND NOISE

- (or maybe you’re a quiet environment, where somebody is sleeping and you can’t turn on the sound)

- Or perhaps you have the bad luck to be with those monsters who talk during films

And even if you can hear the sound fine, you can still benefit from captions:

- Children learning to read

- Somebody learning a foreign language

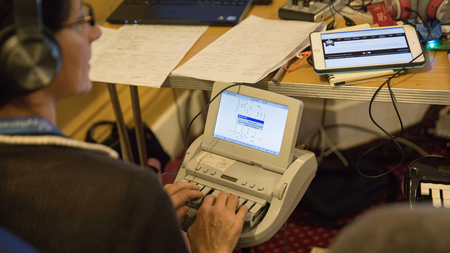

A photo of one of the captioners at PyCon UK 2017, by Mark Hawkins.

And it helps with conferences too!

I’m being captioned right now – literally as I speak! [Monki Gras has live captioning.] This is one of the captioners at PyCon UK, and our experience is that lots of people find it useful during talks, not just the deaf or hard-of-hearing – maybe a word you couldn’t hear, somebody’s speaking with an accent, or you stopped to check twitter halfway through the session.

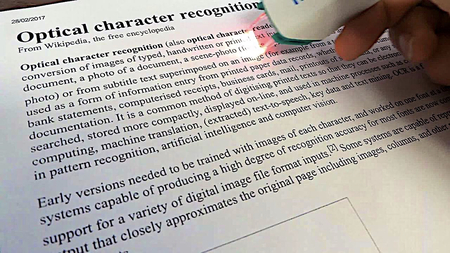

A photo of a handheld OCR scanner, from Wikipedia.

Let’s look at another bit of early technology: optical character recognition, or OCR.

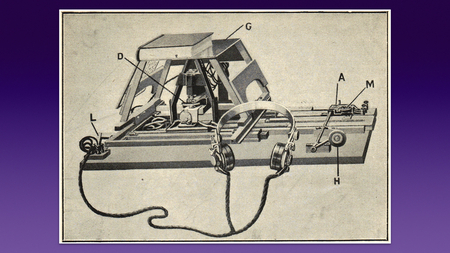

A scanned image of an optophone, taken from Wikipedia.

Early research into OCR was done to help the blind.

This is a machine called an optophone, a device for helping blind people read. You put printed text on the scanner, it identifies the characters and translates them into audio pulses (sort of like Morse code), then plays them through headphones. This was pioneering work for computer vision and text-to-speech synthesis.

These have become widely-used technologies: for making textual versions of scanned documents, Google Books, even those smartphone apps that let you translate signs in a foreign language.

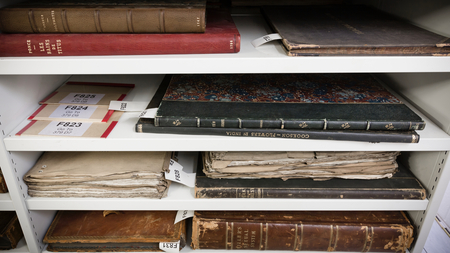

A room full of grey shelves, with books visible on the nearest shelves. Image credit: Wellcome Collection.

And in fact, this is what we do at Wellcome Collection!

For those unfamiliar with Wellcome: we have an archive about human health and medicine. This is one of our “data centres”…

Four shelves, each with a couple of large books on each shelf. Image credit: Wellcome Collection.

…using advanced container technology, like “shelves” and “books”.

Like many institutions, we’re scanning our archives to make them more easily available, and then we use OCR to make them searchable.

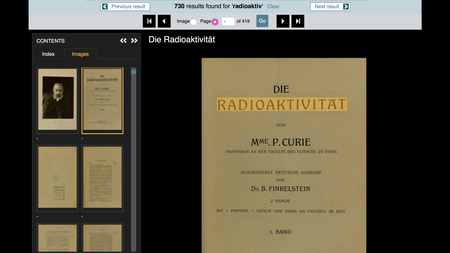

A page from the notebooks of Marie Curie, with a search highlighting instances of the word “radioaktiv”. Image credit: Wellcome Collection.

Here’s one example of our books: a notebook from Marie Curie, freely available to browse online. (Which is preferable to the original, which is slightly radioactive!) And using OCR, we can see that the word “radioaktiv” appears 730 times.

This so cool, but it wouldn’t exist without the pioneering work done into OCR to help blind people.

A silver door handle set against a purple door, with raindrops on the door’s surface. Image credit: MabelAmber on Pixabay, and recoloured by me.

One final example, less high technology and more small convenience: door handles.

Compared to door knobs, handles provide a larger area to grip or rest your hand against, so they’re easier to operate for people with a range of fine motor disabilities that prevent them from grasping small objects.

But they also make it easier if your hands are full, or you’re carrying things – you can lean on the door with an elbow without dropping something. It just makes life a bit easier.

So those are just a few examples of the Curb Cut Effect.

And that’s often where discussion of the Curb Cut Effect stops, which is a shame, because it isn’t just about disability!

Although disabled people are the most visibly excluded, there are plenty of excluded groups to whom this effect applies: women in tech, people of colour, victims of harassment and abuse…

Let’s look at one more example.

In the last few years, there’s been a big uptick in single stall, gender-neutral bathrooms. These are bathrooms that contain their own toilet and sink, maybe a shelf, all in a single private, enclosed space. And their installation has mostly been driven by a desire to accommodate trans and non-binary people who feel uncomfortable in traditionally gendered bathrooms.

And this is great for them… but it helps lots of other people too.

- Parents with children (especially a child of a different gender, especially men)

- Anybody accompanied by a carer

- Men who need baby changing facilities

- Somebody having a period emergency and wants a bit of privacy

So we can take the Curb Cut Effect, and make it stronger:

Making something better for people who are excluded or marginalised makes it better for everyone.

It’s not just about disability.

So why am I telling you all this? Two reasons.

First, these are good stories! They’re little love letters to inclusion, and a nice way to get people talking about inclusion or accessibility.

It’s been really fun to research this talk, and get to go to friends and say, “Hey, did you know this really cool story about the invention of the bendy straw?” (Talk to me in the break if you want to know this one.)

There is a moe serious point.

If you come to a conference titled “Accessible Craft”, you probably already care about inclusion. I don’t need to convince you – you want to do it because it’s the right thing to do.

Unfortunately, things dopn’t happen because they’re “right” or “fair” (what a world that would be!).

We often have to justify the value of inclusion. (If you’re at this conference, you might be the person who does this advocacy, who has to make the business case.)

How often have you heard questions like “Do we have to do this? How many people will use it? Can we really afford it?”

And the Curb Cut Effect is a great tool to remember: it shows the value of inclusion. Spread the cost across a wide group, and changes to support inclusion suddenly seem much more attractive.

It also serves to dispel a powerful myth.

There’s a common suspicion that helping one group must somehow, invisibly, hurt another group. As Spock said, “The needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few”. But in reality, we don’t have to choose!

The Curb Cut Effect shows us this is false: in fact, it shows us the opposite is true. Making the world a better place for a small number of people can make it better for a much wider number too. Yay!

So let’s bring this all together.

I’ve shown you the Curb Cut Effect (repeat), and a handful of my favourite examples. Email. OCR. Door handles. And of course, curb cuts!

But there are many more – go away and try to think of some, maybe even ones in your own work. Keep it in mind, see how you can apply it to the things you build, and remember it the next time you’re asked to justify the value of inclusion.

(Exit to rapturous applause.)