A day out to the Forth Bridge

While clearing out some boxes recently, I found a leaflet from an old holiday. It was a fun day out, and I’d always meant to share the pictures – so here’s the story a day trip from 2016.

I was spending a week in Edinburgh, relaxing and using up some holiday allowance at the end of my last job. My grandparents had suggested I might enjoy seeing the Forth Bridge, because I tend to like railways and railway-related things. I’d heard of the bridge, but I didn’t know that much about it – so while I was nearby, I decided to go take a look.

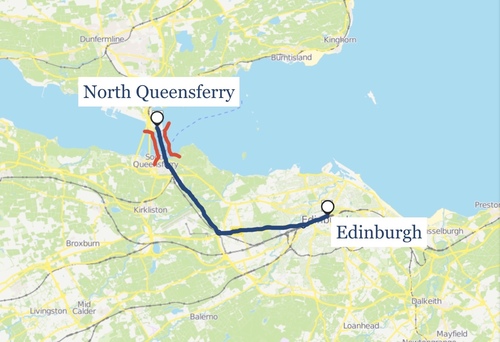

So on a cold December morning, I caught a train from Edinburgh station, up to a village on the north end of the Forth Bridge. I’d never heard of North Queensferry, but what little Googling I’d done suggested it was the best place to go if I wanted to see the bridge up close.

Here’s a map that shows the train line from Edinburgh to the village:

The train takes about 20 minutes, and it crosses the Forth Bridge just at the end of the journey. I wasn’t really aware from the bridge as we went across – not until I got out at the station, wandered into the village, and looked back towards the track.

The name of North Queensferry hints at its former life. It’s on the north side of the narrowest point of the Firth of Forth, which makes it a natural choice if you want to cross the water by boat.

It’s said that in 1068, Saint Margaret of Scotland (wife of King Malcolm III) created the village to ensure a safe crossing point for pilgrims heading to St. Andrew’s. Whether or not she actually created the village, she was a regular user of the ferry service to travel between Dunfurmline (the then-capital of Scotland) and Edinburgh Castle.

For centuries, there were regular crossings of boats and ferries. You can still see a handful of small boats in the harbour, but I’m sure it used to be a lot busier.

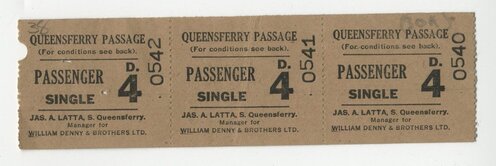

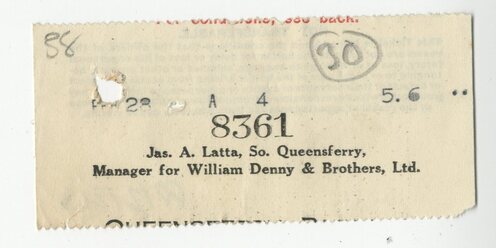

Update, 21 March 2019: It turns out the lighthouse isn’t the only reminder of the ferry service! Chris, an ex-Wellcome colleague and archivist extraordinaire, found some pictures from the Britten-Pears foundation (whose archive and library he runs), including a ticket from the ferry service:

Another lost transport world in @BrittenOfficial’s papers: the ferry over the Forth at Queensferry, which operated until the Forth Road Bridge opened in 1964. Here are 3 passenger tickets plus what I think is a counterfoil from a ticket for a car, from 1950. pic.twitter.com/mpSWZYeEiu

Although most of the boats are gone, one part of the ferry service survives – the lighthouse! This tiny hexagonal tower is the smallest working light tower in the world. It was built in 1817 by Robert Stevenson, a Scottish civil engineer who was famous for building lighthouses. (It was a name I recognised; I loved the story of the Bell Rock Lighthouse when I was younger.)

The light tower sits on the pier, where the ferries used to dock.

Unlike many lighthouses of the time, the keeper didn’t live in the lighthouse itself – but they were still responsible for keeping the flame lit, the oil topped out, and the lighthouse maintained. At night, it would have been an invaluable guide for boats crossing the Firth.

Today, the lighthouse is open to the public. (I think this is where I picked up my leaflet.) You can climb the 24 steps, see the lamp mechanism, and look out over the water. When lit, it gave a fixed white light, with a paraffin-burning lamp – and the large half-dome was the parabolic reflector that turned the candle light into a focused beam.

I wish I’d got a few more photos of the inside of the lighthouse, but it was a pretty small space, and I was struggling to find decent angles. Either way, the lighthouse was an unexpected treat – not something I was expecting at all!

But these days, North Queensferry isn’t known for its ferry service – it’s known for the famous bridge.

In the 1850s, the Edinburgh, Leith and Granton Railway ran a “train ferry” – a boat that carried railway carriages between Granton and Burntisland. There was a desire to build a continuous railway service, and the natural next step was a bridge. After a failed attempt to build a suspension bridge in the 1870s (axed after the Tay Bridge disaster), there was a second attempt in the 1880s. It was opened in March 1890, and it’s still standing today.

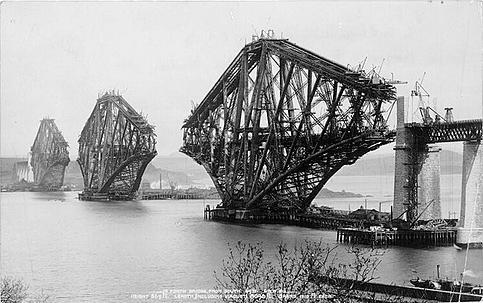

Here’s a photo of its original construction, taken from the North Queensferry hills:

The Forth Bridge is a cantilever bridge. Each structure in the photo above is one of the cantilevers – a support structure fixed at one end – and in the finished bridge the load is spread between them. Spreading the load between multiple cantilevers allows you to build longer bridges, and the Forth Bridge uses this to great effect.

One of the advantages of cantilever bridges is that they don’t require any temporary support while they’re being built – once the initial structures are built, you can expand outwards and they’ll take the weight. Here’s another photo from the construction which shows off this idea:

You can see the shape of the bridge starting to expand out from the initial structure.

The Forth Bridge is famous for a couple of reasons. When it was built, it was the longest cantilever span in the world (not bested for another twenty-nine years, and still the second longest). It was also one of the first major structures in Britain to use steel – 55,000 tonnes in the girders, along with a mixture of granite and other materials in the masonry.

You get a great view of the finished bridge from inside the lighthouse:

As I wandered around the village, I got lots of other pictures of the rail bridge. These are a few of my favourites:

The last one was my favourite photo of the entire holiday, and I have a print of it on the wall of my flat. Blue skies galore, which made for a lovely day and some wonderful pictures – even if it’s not what you expect from a Scottish winter!

What’s great about wandering around the village is that you can see the bridge from all sorts of angles, not just from afar – you can get up and personal. You can see the approach viaduct towering over the houses as it approaches the village:

And you can get even closer, and walk right underneath the bridge itself. Here’s what part of the viaduct holding up the bridge looks like:

They’re enormous – judging by the stairs, it’s quite a climb up!

And you can look up through the girders, and see the thousands of beams that hold the bridge together:

It’s been standing for over a century, so I’m sure it’s quite safe – but it was still a bit disconcerting to hear a rattle as trains passed overhead!

I spent quite a while just wandering around under the bridge, looking up in awe at the structure. As you wander around the village, you never really get away from it – it always stands tall in the background. (Well, except when I popped into a café for some soup and a scone.)

After the rail bridge was built, the ferry crossings continued for many years – in part buoyed by the rise of personal cars, which couldn’t use the railway tracks. But it didn’t last – in 1964, a second bridge was built, the Forth Road Bridge – and it replaced the ferries. The day the bridge opened, the ferry service closed after eight centuries of continuous crossings.

When I visited in 2016, the Road Bridge was still open to cars. At the time, there was a second bridge under construction, but not yet open to the public – the Queensferry Crossing opened half a year later after my visit. The original Road Bridge is a public transport link (buses, cyclists, taxis and pedestrians), and the new bridge carries everything else.

Three bridges in a single day! The other bridges were on the other side of the bay, so I had to walk along the water’s edge to see them. Here’s a photo from midway along, with old and new both visible:

These are both suspension bridges, whereas the rail bridge is a cantileverl.

Like the rail bridge, you can get up and close with the base of the road bridge. Here’s an attempt at an “artsy” shot of the bridge receding into the distance, with sun poking through the base:

And another “artsy” shot with more lens flare, and both the road bridges in the shot. I love the detail of the underside on the nearer bridge.

Here’s the start of the bridge on the north side, starting to rise up over the houses:

And one more close-up shot of one of the supports:

Eventually it started getting dark, so I decided to head home. I considered walking back through North Queensferry to the station, but I decided to have a crack at crossing the road bridge instead, and catching the train from the other side. You can walk across it, although it’s nearly 2.5k long!

As you climb up to the bridge, I got some wonderful views back over the village, and in particular towards the rail bridge I’d originally come to see:

I didn’t take many photos from the bridge itself, although it’s a stunning view! It was extremely cold and windy, and I didn’t want to risk losing my camera while trying to take a photo. Here’s one of the few photos I did take, which I rather like. I took it near the midpoint, with the rail bridge set against a cloudy sky. (I’d forgotten about it until I came to write this post!)

Safely across the bridge, I weaved my way through South Queensferry, found the station, and caught a train back to Edinburgh.

I didn’t plan this trip when I decided to visit Scotland, but over two years later, I still have fond memories of the day out. If you’re ever nearby and you like looking at impressive structures, it’s worth a trip. I’m glad I have pictures, but it’s hard to capture the sheer size and scale of a bridge this large – so if you have a chance, do visit in person.