Creating a locking service in a Scala type class

A few weeks ago, Robert (one of my colleagues at Wellcome) and I wrote some code to implement locking. I’m quite pleased with the code we wrote, and the way we do all the tricky logic in a type class. It uses functional programming, type classes, and the Cats library.

I’m going to walk through the code in the post, but please don’t be intimidated if it seems complicated. It took us both a week to write, and even longer to get right!

I’m not expecting many people to use this directly. You can copy/paste it into your project, but unless you have a similar use case to us, it won’t be useful to you. Instead, I hope you get a better understanding of how type classes work, how they can be useful, and the value of sans-IO implementations.

The problem

Robert and I are part of a team building a storage service, which will eventually be Wellcome’s permanent storage for digital records. That includes archives, images, photographs, and much more.

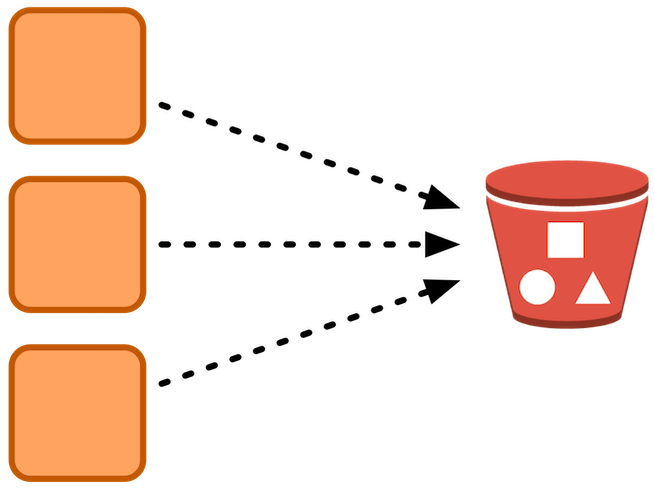

We’re saving files to an Amazon S3 bucket1, but Amazon doesn’t have a way to lock around writes to S3. If more than one process writes to the same location at the same time, there’s no guarantee which will win!

Our pipeline features lots of parallel workers – Docker containers running in ECS, and each container running multiple threads. We want to lock around writes to S3, so that only a single process can write to a given S3 location at a time. We already verify files after they’ve been written, and locking gives an extra guarantee that a rogue process can’t corrupt the archive. Because S3 doesn’t provide those locks for us, we have to manage them ourselves.

This is one use case – there are several other places where we need our own locking. We wanted to build one locking implementation that we could use in lots of places.

The idea

We already had an existing locking service that used DynamoDB as a backend. It creates locks by writing a row for each lock, and doing a conditional update “only store this row if there isn’t already a row with this lock ID”. If the conditional updated failed, we’d know somebody else was holding the lock.

This code worked fine, but it was closely tied to DynamoDB, and that caused issues.

It was slow and fiddly to test – you needed to set up a dummy DynamoDB instance – and if you were calling the locking service, you needed that test setup as well. It was also closely tied to the DynamoDB APIs, so we couldn’t easily extend or modify it to work with a different backend (for example, MySQL).

We wanted to try writing a new locking service that wasn’t tied to DynamoDB. We’d separate out the locking logic and the database backend, and write something that was easy to extend or modify.

This is the API in the original service which were were trying to replicate:

lockingService.withLocks(Set("1", "2", "3")) {

// do some stuff

}

The idea of doing it in a type class (so it wasn’t tied to a particular database implementation) isn’t new.

I first came across this idea when working on hyper-h2, an HTTP/2 protocol stack for Python that’s purely in-memory. It only operates on bytes, and doesn’t have opinions about I/O or networking, so it can be reused in a variety of contexts. hyper-h2 is part of a wider pattern of sans-IO network protocol libraries, and many of the same benefits apply here.

Managing individual locks

First we need to be able to manage a lock around a single resource. We assume the resource has some sort of identifier, which we can use to distinguish locks.

We might write something like this (here, a dao is a data access object):

trait LockDao[Ident] {

def lock(id: Ident)

def unlock(id: Ident)

}

This is a generic trait, which manages acquiring and releasing a single lock. It has to decide if/when we can perform each of those operations.

We can create implementations with different backends that all inherit this trait, and which have different rules for managing locks. A few ideas:

- A DynamoDB-backed LockDao for use in production applications

- An in-memory LockDao for use in tests

- A LockDao that expires locks after a certain period if not explicitly unlocked

The type of the lock identifier is a type parameter, Ident. An identifier might be a string, or a number, or a UUID, or something else – we don’t have to decide here.

Sometimes we need to acquire more than one lock at once, which needs multiple calls to lock() – and then the caller has to remember which locks they’ve acquired to release them. To make it simpler for the caller, we’ve added a second parameter – a context ID – to track which process owns a given lock. A single call to unlock() releases all the locks owned by a process.

Here’s what that trait looks like:

trait LockDao[Ident, ContextId] {

def lock(id: Ident, contextId: ContextId)

def unlock(contextId: ContextId)

}

As before, the context ID could be any type, so we’ve made it a type parameter, ContextId.

Now let’s think about what these methods should return. We need to tell the caller whether the lock/unlock succeeded.

We probably want some context, especially if something goes wrong – so more than a simple boolean. We could use a Try or a Future, but that doesn’t feel quite right – we expect lock failures sometimes, and it’d be nice to type the errors beyond just Throwable.

Eventually we settled upon using an Either, with case classes for lock/unlock failures that include some context for the operation in question, and a Throwable that explains why the operation failed:

trait LockDao[Ident, ContextId] {

type LockResult = Either[LockFailure[Ident], Lock[Ident, ContextId]]

type UnlockResult = Either[UnlockFailure[ContextId], Unit]

def lock(id: Ident, contextId: ContextId): LockResult

def unlock(contextId: ContextId): UnlockResult

}

trait Lock[Ident, ContextId] {

val id: Ident

val contextId: ContextId

}

case class LockFailure[Ident](id: Ident, e: Throwable)

case class UnlockFailure[ContextId](contextId: ContextId, e: Throwable)

There’s also a generic Lock trait, which holds an Ident and a ContextId. Implementations can return just those two values, or extra data if it’s appropriate. (For example, we have an expiring lock that tells you when the lock is due to expire.)

Now we need to create implementations of this trait!

Creating an in-memory LockDao for testing

Somebody who uses the LockDao can ask for an instance of that trait, and it doesn’t matter whether it’s backed by a real database or it’s just in-memory. So when we’re testing code that uses the LockDao – but not testing a LockDao implementation specifically – we can use a simple, in-memory implementation. This makes our tests faster and easier to manage!

Let’s create one now. Here’s a skeleton to start with:

class InMemoryLockDao[Ident, ContextId] extends LockDao[Ident, ContextId] {

def lock(id: Ident, contextId: ContextId): LockResult = ???

def unlock(contextId: ContextId): UnlockResult = ???

}

Because this is just for testing, we can store the locks as a map. When somebody acquires a new lock, we store the context ID in the map. Here’s what that looks like:

case class PermanentLock[Ident, ContextId](

id: Ident,

contextId: ContextId

) extends Lock[Ident, ContextId]

class InMemoryLockDao[Ident, ContextId] extends LockDao[Ident, ContextId] {

private var currentLocks: Map[Ident, ContextId] = Map.empty

def lock(id: Ident, contextId: ContextId): LockResult =

currentLocks.get(id) match {

case Some(existingContextId) if contextId == existingContextId =>

Right(

PermanentLock(id = id, contextId = contextId)

)

case Some(existingContextId) =>

Left(

LockFailure(

id,

new Throwable(s"Failed to lock <$id> in context <$contextId>; already locked as <$existingContextId>")

)

)

case None =>

val newLock = PermanentLock(id = id, contextId = contextId)

currentLocks = currentLocks ++ Map(id -> contextId)

Right(newLock)

}

def unlock(contextId: ContextId): UnlockResult = ???

}

We have to remember to look for an existing lock, and compare it to the lock that’s requested. It’s fine to call lock() if you already have the lock, but you can’t lock an ID that somebody else owns.

Unlocking is much simpler: we just remove the entry from the map.

class InMemoryLockDao[Ident, ContextId] extends LockDao[Ident, ContextId] {

def lock(id: Ident, contextId: ContextId): LockResult = ...

def unlock(contextId: ContextId): UnlockResult = {

currentLocks = currentLocks.filter { case (_, lockContextId) =>

contextId != lockContextId

}

Right(Unit)

}

}

This gives us a LockDao implementation that’s pretty simple, and we can use whenever we need a LockDao in tests.

Because it’s only for testing, it doesn’t need to be thread-safe or especially robust. This code is quite simple, so we’re more likely to get it right. When a caller uses this in tests, they can trust the LockDao is behaving correctly and focus on how they use it, and not worry about bugs in the locking code.

Here’s what it looks like in practice:

import java.util.UUID

val dao = new InMemoryLockDao[String, UUID]()

val u1 = UUID.randomUUID

println(dao.lock(id = "1", contextId = u1)) // succeeds

println(dao.lock(id = "1", contextId = UUID.randomUUID)) // succeeds

println(dao.lock(id = "2", contextId = UUID.randomUUID)) // fails

println(dao.unlock(contextId = u1))

println(dao.lock(id = "1", contextId = UUID.randomUUID)) // succeeds

We also have a small number of tests to check it behaves correctly:

- It locks an ID/context pair

- You can’t lock the same ID under different contexts

- You can lock different IDs under the same context

- You can unlock all the IDs under the same context

- When an ID is unlocked, it can be relocked in a new context

Because there’s no I/O involved, those tests take a fraction of a second to run.

Creating a concrete implementation of LockDao

Because we work primarily in AWS, we’ve created a LockDao implementation that uses DynamoDB as a backend. This is what we use when running in production.

It fulfills the same basic contract, but it has to be more complicated. It calls the DynamoDB APIs, makes conditional updates, and it expires a lock after a fixed period if it hasn’t been released. If a worker crashes before it can release its locks, we want the system to recover automatically – we don’t want to have to clean up those locks by hand.

I’m not going to walk through it, but you can see this code in our GitHub repo (link at the end of the post).

Creating the locking service

Now let’s build a locking service. You pass it a set of identifiers and a callback. It has to acquire a lock on each of those identifiers, get the result of the callback, then release the locks and return the result.

Here’s a stub to start us off:

trait LockingService[Ident] {

def withLocks(ids: Set[Ident])(callback: => ???) = ???

}

For now, let’s put aside the return type of the callback, and acquire a lock. We’ll need a lock dao (which can be entirely generic), and a way to create context IDs:

trait LockingService[LockDaoImpl <: LockDao[_, _]] {

implicit val lockDao: LockDaoImpl

def withLocks(ids: Set[lockDao.Ident])(callback: => ???) = ???

def createContextId: lockDao.ContextId

}

We’re asking implementations to tell us how to create a context ID, because the type of context ID will vary, as will the rules for creation. Maybe it’s a worker ID, or a thread ID, or a random ID used once and discarded immediately after.

Then we need to acquire the locks on all the identifiers we’ve received. If we get them all, we can call the callback – but if any of the locks fail, we should release anything we’ve already locked and return without invoking the callback.

Let’s write a method for acquiring the locks:

import grizzled.slf4j.Logging

trait FailedLockingServiceOp

case class FailedLock[ContextId, Ident](

contextId: ContextId,

lockFailures: Set[LockFailure[Ident]]) extends FailedLockingServiceOp

trait LockingService[LockDaoImpl <: LockDao[_, _]] extends Logging {

...

type LockingServiceResult = Either[FailedLockingServiceOp, lockDao.ContextId]

def getLocks(

ids: Set[lockDao.Ident],

contextId: lockDao.ContextId): LockingServiceResult = {

val lockResults = ids.map { lockDao.lock(_, contextId) }

val failedLocks = getFailedLocks(lockResults)

if (failedLocks.isEmpty) {

Right(contextId)

} else {

unlock(contextId)

Left(FailedLock(contextId, failedLocks))

}

}

private def getFailedLocks(

lockResults: Set[lockDao.LockResult]): Set[LockFailure[lockDao.Ident]] =

lockResults.foldLeft(Set.empty[LockFailure[lockDao.Ident]]) { (acc, o) =>

o match {

case Right(_) => acc

case Left(failedLock) => acc + failedLock

}

}

private def unlock(contextId: lockDao.ContextId): Unit =

lockDao

.unlock(contextId)

.leftMap { error =>

warn(s"Unable to unlock context $contextId fully: $error")

}

}

The main entry point is getLocks(), which gets both the IDs and the context ID we’ve created. As in the InMemoryLockDao, this returns an Either[…], so we get nice context about any locking failures.

First we call lockDao.lock(…) on every ID, which gives us a list of LockResults. We look for any failures with getFailedLocks() – if there are any, we try to release the locks we’ve already taken, and return a Left. If all the locks succeed, we get a Right.

The unlocking happens in unlock(). It attempts to unlock everything, but an unlock failure just gets a warning in the logs, not a full-blown error. We’re already bubbling up an error for the locking failure, and we didn’t think it worth exposing those extra errors. And if the callback succeeds but the unlocking fails, the operation as a whole is still a success and worth returning to the caller.

Then we have to actually invoke the callback, and this bit gets interesting. We want this service to be very generic, and handle different types of function. The callback might return a Future, or a Try, or an Either, or something else. We want to preserve that return type, and combine it with possible locking errors.

So we added another pair of type parameters:

trait LockingService[Out, OutMonad[_], ...] {

...

type Process = Either[FailedLockingServiceOp, Out]

def withLocks(

ids: Set[lockDao.Ident])(

callback: => OutMonad[Out]): OutMonad[Process] = ???

}

We’re starting to get into code that uses more advanced functional programming, and in particular the Cats library. Robert and I were reading the book Scala with Cats as we wrote this code. It’s a free ebook, and I’d recommend it if you want more detail.

Let’s go through this code carefully.

We’ve added two new type parameters: Out and OutMonad[_], so the return type of our callback is OutMonad[Out]. What’s a monad?

This is the definition that works for me: a type F is a monad if:

-

It has a type constructor

F[_]that takes exactly one type parameter. -

There’s a function that takes a value of any type

Aand produces a value of typeF[A]. This is called a monadic unit. -

If you have a function

A => F[B], and a functionB => F[C], you can combine these functions to get a single functionA => F[C]. This is called monadic composition.

Some examples of monads in Scala include List[_], Option[_] and Future[_]. They all take a single type parameter, have a monadic unit, and you can compose them with flatMap.

So we expect our callback to return a monad wrapping another type. Inside the service, we’ll get an Either which contains the result of the callback or the locking service error, and then we’ll wrap that Either in the monad type. We’re preserving the monad return type of the callback.

For example, if our callback returns Future[Int], then OutMonad would be Future and Out would be Int. The withLocks(…) method then returns Future[Either[FailedLockingServiceOp, Int]].

But what if our callback doesn’t return a monad? What if it returns a type like Int or String? Here we’ll use a bit of Cats: we can imagine these types as being wrapped in the identity monad, Id[_]. This is the monad that maps any value to itself, i.e. id(a: A) = a.

So even if the callback code isn’t wrapped in an explicit monad, the compiler can still assign the type parameter OutMonad, by imagining it as Id[_].

So now we know what type our callback returns, let’s actually call it inside the locking service. For now, assume we’ve already successfully acquired the locks, and we want to run the callback.

import cats.MonadError

case class FailedProcess[ContextId](contextId: ContextId, e: Throwable)

extends FailedLockingServiceOp

trait LockingService[Out, OutMonad[_], ...] {

...

type Process = Either[FailedLockingServiceOp, Out]

def unlock(contextId: ContextId): UnlockResult = ...

type OutMonadError = MonadError[OutMonad, Throwable]

import cats.implicits._

def safeCallback(contextId: lockDao.ContextId)(

callback: => OutMonad[Out]

)(implicit monadError: OutMonadError): OutMonad[Process] = {

val partialResult: OutMonad[Process] = callback.map { out =>

unlock(contextId)

Either.right[FailedLockingServiceOp, Out](out)

}

monadError.handleError(partialResult) { err =>

unlock(contextId)

Either.left[FailedLockingServiceOp, Out](FailedProcess(contextId, err))

}

}

}

We’re bringing in more stuff from Cats here. The type we’ve just imported, MonadError, gives us a way to handle errors that happen inside monads – for example, an exception thrown inside a Future.

We call the callback, and wait for it to return (for example, a Future doesn’t return immediately). If it returns successfully, we map over the result, unlock the context ID, and wrap the result in a Right. We’ve imported cats.implicits._ so we can map over OutMonad and preserve its type. This the happy path.

If something goes wrong, we use the MonadError to handle the error, unlock the context ID, and then wrap the result in a Left. Using this Cats helper ensures we handle the error correctly, and it gets wrapped in the appropriate monad type at te end. This is the sad path.

Either way, we’re waiting for the callback to return and then releasing the locks.

If we had a concrete type like Future or Try, we’d know how to wait for the result. Instead, we’re handing that off to Cats.

Now we have all the pieces we need to actually write out withLocks method, and here it is:

import cats.data.EitherT

trait LockingService[Out, OutMonad[_], ...] {

...

type LockingServiceResult = Either[FailedLockingServiceOp, lockDao.ContextId]

def getLocks(

ids: Set[lockDao.Ident],

contextId: lockDao.ContextId): LockingServiceResult = ...

def withLocks(ids: Set[lockDao.Ident])(

callback: => OutMonad[Out]

)(implicit m: OutMonadError): OutMonad[Process] = {

val contextId: lockDao.ContextId = createContextId

val eitherT = for {

contextId <- EitherT.fromEither[OutMonad](

getLocks(ids = ids, contextId = contextId)

)

out <- EitherT(safeCallback(contextId)(callback))

} yield out

eitherT.value

}

}

Hopefully you recognise all the arguments to the function – the IDs to lock over, the callback, and the implicit MonadError (which will be created by Cats).

That EitherT in the for comprehension is another Cats helper. It’s an Either transformer – if you have a monad type F[_] and types A and B, then EitherT[F[_], A, B] is a thin wrapper for F[Either[A, B]]. It lets us easily swap the Either and the F[_].

In the first case, it takes the result of getLocks() and wraps it in OutMonad.

If getting the locks succeeds, then it calls safeCallback() and wraps that in an EitherT as well. Once that returns, it extracts the value of the underlying OutMonad[Either[_, _]] and returns that result.

And that’s the end of the locking service! In barely a hundred lines of Scala, we’ve implemented all the logic for a locking service – and it’s completely independent of the underlying database implementation.

Putting the locking service to use

We can combine the generic locking service with the in-memory lock dao, and get an in-memory locking service. Because all the logic is in the type class, this is really short:

import java.util.UUID

val lockingService = new LockingService[String, Try, LockDao[String, UUID]] {

override implicit val lockDao: LockDao[String, UUID] =

new InMemoryLockDao[String, UUID]()

override def createContextId: UUID =

UUID.randomUUID()

}

This is perfect for testing the locking service logic – because it’s in-memory, it runs really quickly, and we can write lots of tests to check it behaves correctly. Our tests cases include checking that it:

- Acquires the locks in the underlying dao

- Returns the result of a successful callback

- Returns a failure if you try to re-lock an already locked identifier, and preserves the original locks

- Allows you to nest locks

- Releases the lock when the callback completes (both success and failure), and allows you to re-lock

- Releases all of its locks if it fails to lock a complete set of IDs

- Succeeds even if unlocking fails

And those tests run in a fraction of a second! Because everything happens in memory, it’s incredibly fast.

And when we have code that uses the locking service, we can drop in the in-memory version for testing that, as well. It makes tests simpler and cleaner elsewhere in the codebase.

When we want an implementation to write in production, we can combine it with a LockDao implementation and get a new locking service implementation. This is the entirety of our DynamoDB locking service:

class DynamoLockingService[Out, OutMonad[_]](

implicit val lockDao: DynamoLockDao)

extends LockingService[Out, OutMonad, LockDao[String, UUID]] {

override protected def createContextId(): lockDao.ContextId =

UUID.randomUUID()

}

This is the beauty of doing it in a type class – we can swap out the implementation and not have to rewrite any of the tricky lock/unlock logic. It’s a really generic and reusable implementation.

Putting it all together

All the code this post was based on is in a public GitHub repository, wellcomecollection/scala-storage, which is a collection of our shared storage utilities (mainly for working with DynamoDB and S3). These are the versions I worked from:

-

Managing individual locks

-

Creating an in-memory LockDao for testing

-

Creating a concrete implementation of LockDao

-

Creating the locking service

-

Putting the locking service to use

I’ve also put together a mini-project you can download with the code from this blog post alone. It has both the type classes, the in-memory LockDao implementation, and a small example that exercises both classes. All the code linked above (and in this post) is available under the MIT licence.

Writing this blog post was a useful exercise for me. If I want to explain this code, I have to really understand it. There’s no room to handwave something and say “this works, but I’m not sure why”.

And it makes the code better too! As I was writing this post, I spotted several places where the original code was unclear or inefficient. I’ll push those fixes back to the codebase – so not only is this blog post an explanation for future maintainers, but the code itself is clearer as well.

I can’t do this sort of breakdown for all the code I write, but I recommend it if you’re every writing especially complex or tricky code.

-

Eventually every file will be stored in multiple S3 buckets, all with versioning and Object Locks enabled. We’ll also be saving a copy in another geographic region and with another cloud provider, probably Azure. ↩︎