Building trust in an age of suspicious minds

This is a talk I gave on Saturday as the opening keynote of PyCon UK 2018.

I was already planning to do a talk about online harassment, and Daniele, the conference director, encouraged me to expand the idea, and turn it into a talk about positive behaviour. This is my abstract:

In 2018, trust is at a low. Over the past several decades, trust has declined – fewer and fewer people trust each other, and the reputation of big institutions (government, media, politicians, even non-profits) is in tatters.

What happened?

In this talk, I’ll explain how the design of certain systems have been exploited for abuse, and this has corroded our trust – and conversely, how we can build environments that encourage and sustain good behaviour.

The talk was recorded, and thanks to the wizardry of Tim Williams, it was on YouTube within a day:

You can read the slides and transcript on this page, or download the slides as a PDF. The transcript is based on the captions on the YouTube video, with some light editing and editorial notes where required.

I prepped this talk at fairly short notice, and it wasn’t as polished as I’d like. There’s a lot of um’ing and ah’ing. If I end up doing this talk again, I’d love to go back and get some more practice.

[Ed. I was introduced by Daniele Procida, the conference director.]

Based on the cover art of the Elvis single.

Thanks for that introduction. As Daniele said, my name is Alex, I’m a software developer at the Wellcome Trust in London, and I help organise this conference. It’s a pleasure to be opening this year’s conference, and I really hope you all have a great time.

The reason I was asked to do this talk is that I spent my time thinking about a lot of ways that systems can be exploited for harassment, abuse, and to do nasty things. (Which is a polite way of saying I’m good at breaking stuff, so the fact we’ve made the projector work on the first try is a huge achievement. If nothing else goes well this morning, I’ll take that.)

By thinking about how things can be exploited and broken, you often come to them with a very defensive mindset. You’re thinking about damage control – how do I limit the potential of harm?

Daniele challenged me to flip that on its head. Could you go the other way, and not just design a system that prevents bad behaviour, but actually encourages good behaviour? I started thinking about good behavior, how you build that, how you encourage that, and what I started thinking about was trust.

Trust is really important. It underpins all of our working relationships – whether that’s with other people, with our tools, with our users (the people we’re building systems for).

If we feel like we trust somebody, we feel like we can rely on them, we can cooperate with them, we can believe they will actually do what they say they will. It gives us a sense of security. It means we’re not looking over our shoulder, looking for the next mistake or betrayal, trying to work out what’s going to go wrong.

So we’re going to talk about trust today, because it’s a foundation of good working relationships, and the other positive behaviours that they foster.

But trust is kind of a nebulous thing, isn’t it?

We sort of know when we trust somebody, we know when we don’t – I think it’s helpful to start by having a definition of trust.

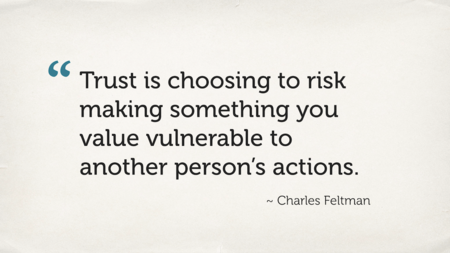

Charles Feltman has written a book called The Thin Book of Trust that has a definition I really like:

Trust is choosing to risk making something you value vulnerable to another person’s actions.

So let’s break down that definition.

Trust is choosing to risk – it’s a risk assessment. We look at our past experiences with somebody, and we decide if we want to take the risk. If we trust somebody, we probably do want to take that risk; and if we don’t trust them, then we don’t.

And it’s taking something you value – and we value all sorts of things. Money, happiness, fulfillment, not being fired from our jobs, not being booed off a stage in front of 400 people.

And finally, we’re making it vulnerable. We’re giving up some control over the thing we care about.

In the software industry, we often think about vulnerability as a really bad thing, because we think about it in the context of security vulnerabilities. It’s a hack, it’s got to be patched and closed off immediately, and that’s right – but vulnerability is also really important.

If you have vulnerability, you have the opportunity to progress, opportunity for growth. You need vulnerability to be able to grow, and it’s a really important part of trust.

So that’s the definition of trust we’re going to use today.

We’re usually pretty good at articulating when we don’t trust somebody.

Hands up in the audience: who has ever thought “I just don’t trust them”?

I think that’s pretty much the entire audience. [Ed. I was looking at a room full of raised hands.]

If I asked you all, you all had a good reason, right? Maybe there was a lie, there was an incident, they were mean, you had some gossip…

But what if I asked you to go in the other direction? Think of somebody you really trust.

If I asked you “why do you trust them”, it feels like a harder question, doesn’t it? We’re often aware that we trust somebody, but it can be hard to pinpoint the moment when that happened. How do we go from the state of “somebody we just know” to “somebody we actually trust”?

Because trust isn’t something you can tell somebody to do, you can’t ask for it, and as much as Facebook’s marketing marketing team would love, you can’t buy it!

That’s not great, is it? If trust is such an important thing, we shouldn’t just be passive participants. That’s what I want to look at today. I want to look at how we take an active role in the formation of trust. How do we actively build trust for ourselves?

So what’s the state of trust in 2018, a year of only happiness and rainbows? How much do we trust in each?

Image: Easter Fire, by claus-heinrichcarstens on Pixabay. CC0.

If we go on Twitter, in the six minutes that I’ve been speaking, there have probably been about six years worth of news. It feels like the world is on fire (sometimes literally), and the unfortunate thing is it seems like that often isn’t any trust.

Studies consistently show that trust in each other – trust in individuals – is declining. And trust in big institutions – businesses, governments, nonprofits, the media – we’re not trusting those institutions as much either. Those are places that we might have once looked to for trust and guidance.

You wouldn’t inspect the credentials of every journalist in a newspaper; you’d trust the newspaper would do that for you. You trust they’d so some fact checking. And we now longer trust that they will do that.

So how did we get here?

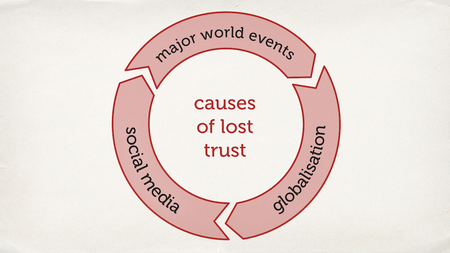

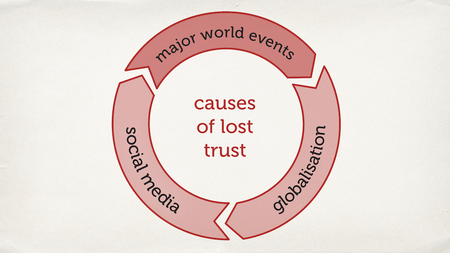

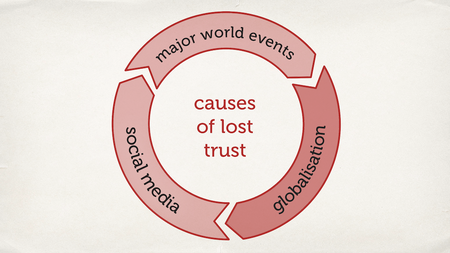

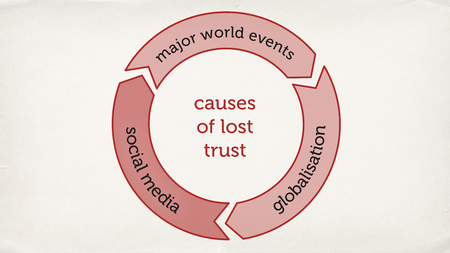

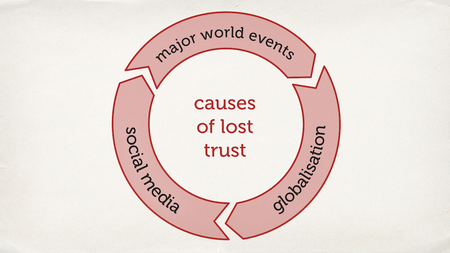

I think it was caused by three major trends in the last 10–15 years:

- Major world events

- The downsides of globalisation

- Social media

So let’s go through them in turn.

Some significant events.

If you look at the last twenty years, there have been several major turning points where we stopped trusting people.

- The first was the September 11th attacks in 2001 and the subsequent response by the governments of the world.

- Then the faulty rationale for the war in Iraq. “45 minutes to deployment of weapons of mass destruction.”

- The 2008 financial collapse, which we’re still seeing the fallout of ten years later.

- In this country (and I’m very jealous of our overseas attendees) is the Brexit referendum and all the following “negotiations”. [Ed. Yes, I used finger quotes.]

All of these things these events leave people feeling angry, feeling bitter, feeling divided, suspicious, sceptical. Those are a really poor recipe for trust. When we have all these heated emotions, it’s not surprising that we don’t trust some of these big institutions as much.

One thing that’s interesting as well – I think we might be in the middle of another seismic trust event. For years, there have been a trickle of stories about bad things happening at tech companies – probably companies that some of us work at. Privacy violations at Facebook, location tracking at Google, safety violations at Uber – and it feels to me like that trickle is starting to become a flood. Every week I look at the headlines, and I see some other bad thing that’s happening another tech company

I do wonder if we’ll look back in a couple of years, and see 2018 as the point where trust in tech started to falter. Maybe one day we could be aspire to be as trusted as bankers. [Ed. The audience laughed, but I’m serious.]

Those are some of the major world events that have already happened, and that we need to be worrying about.

Second let’s talk about the downsides of globalisation.

On the one hand, globalisation is wonderful. It’s made the world a smaller, more interconnected place. It’s the reason we have such a diverse group of attendees here today.

But it’s not without its downsides, and a lot of the time those benefits aren’t evenly distributed. Too many people, too many workers, too many families feel like they’re bearing all the brunt of globalisation, and they’re not feeling any of the benefits.

That could be in things like automation and job losses (which again, the tech industry is sort of responsible for). Or things like open borders, mass movement of people, the changing of cultures. People are afraid – they’re worried about their economic security, their job prospects – and they lash out. This manifests itself in things like nationalism and xenophobia, and older audience members might remember a time when those were considered fringe political movements. Happier days.

With the advent of social media, a lot of those fringe movements have become mainstream.

We’re seeing now the true effect of having a firehose of unfiltered information and outrage piped directly to a screen in our pockets. Social media stirs up anger, it provokes hate, it spreads lies.

When I was younger, there was a quote my grandfather loved: “A lie can get halfway around the world before the truth has got its boots on. Not only has the Internet made the lie go a lot faster, it’s also completely mangled that quote. If you type that quote into Google, you will find at least 15 different people who it’s attributed to, and that cannot possibly be right!

One aspect of this is “fake news”. It’s become a bit of a catch phrase the last year or so as a catch-all term for “everything that Donald Trump doesn’t like” but there is—

(I started saying “legitimate fake news”, which is surely an oxymoron. Let’s try that again.)

There is “news” that is really fake. You can go on the Internet now, you can find a website that looks like a legitimate news source with not sentences that contain words that you think are facts – and it’s entirely wrong.

This makes it much harder now to determine true from false when we’re reading the news. Not only that, social media has eroded our ability to do so, by presenting us with a firehose. It’s a denial-of-service attack on our ability to make trust decisions, because there’s just so much stuff we have to deal with.

So these are the three things that have led to an erosion of trust:

- Major world events

- The downsides of globalisation

- The advent and spread of social media

These three trends all build on each other. They accelerate each other, and perhaps it’s not so surprising that we don’t trust each other as much as we used to.

But it’s not like trust is gone entirely. We can still be very trusting people – let’s look at a few examples.

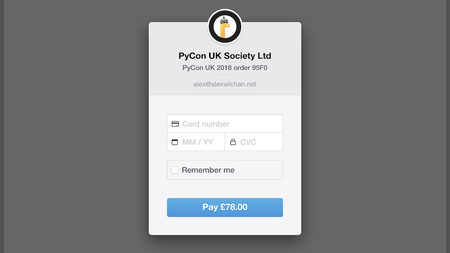

First: online banking.

If you paid for your own ticket for the conference, you’ll have seen a screen that looked a bit like this, and you all happily put in your credit card details and clicked the pay button. (At least, it seems like you did, because you’re all here.) And we gave you a ticket.

You put in your credit card details, and you trusted that we were going to send that to a credit card provider and use it to pay for your ticket – and we weren’t going to use it to buy Bitcoins, we weren’t going to send it to a server in Russia, it wouldn’t be sent to my personal Gmail.

We trust that we can put our banking details into website into the Internet, and it’s going to work. If you think about it, that’s a really recent thing. Not so many years ago, that would have been a very unusual thing to do, and yet today we just take it granted.

I’m sure this driver is just making sure she’s crossing the road safely. What an upstanding fine citizen!

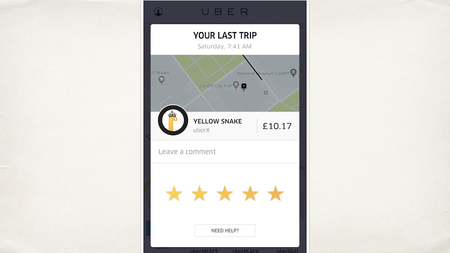

Another example: ride-sharing.

When I was younger, I was taught “stranger danger”. You don’t give out your personal details on the Internet; you don’t get into other people’s cars; you don’t give out your location. And now it’s routine for people to give out their personal details on the Internet… to a stranger… to invite them to their location… so that we can get in their car.

And then we pay them for it.

And many people even trust this more than they trust traditional black cabs or public transport. This book isn’t that old – this is another weird inversion of trust.

The final one: Airbnb.

How many of you are staying tonight not in a licensed hotel chain, not a registered B&B, not in Mrs. Potts but you’ve gone to a stranger’s home? [Ed. Mrs. Potts is a Cardiff hostel that’s fairly popular among PyCon UK attendees. I saw a few hands in the audience.]

You’ve picked a random stranger on the Internet, and said, “Yes, I will stay in your home, and I trust that you will not steal my things or turn out to be a bloodthirsty axe murderer or kidnap me so that I never seen again.”

And likewise, your hosts – they’ve invited you, a suspicious programmer type going to “PyCon”. They trust that you’re going to come into their home and sleep there and you won’t steal their things, you won’t ransack their home, and that it’s safe to invite an (almost literally) revolving door of strangers into their home.

Again, something that we would have thought was quite odd a few years ago.

This isn’t an accident. Just because you don’t trust politicians less doesn’t mean that you now randomly trust strangers on the Internet.

The reason we trust these things is because people took explicit steps to make that happen – whether that’s the green padlock icon or ratings in Uber or Airbnb verification – with all of these things, somebody did explicit work to make a system you could trust.

We can do the same. Trust clearly isn’t impossible. There’s still a lot of trust in these things, but also in the way society functions, and so we can actively build trust as well.

So let’s talk about that now. How do you build trust?

One exercise that is often used to build trust is this one. Some of you might be familiar with it if you’ve been on a “team-building” day [Ed. Again, finger quotes].

It’s called trust fall. One partner closes their eyes and falls backwards, and they know the other person is going to catch them, so they trust the other person.

(As long as you do catch them. I did this for a small group at work on Monday, and one person said not only had they done this exercise, but their partner had dropped them. Clearly a very effective exercise for them!)

Trust is not built in one shot interactions. It’s also not built knowing exactly what’s going to happen, and knowing that they’ll catch you because if not they’ll be in trouble for breaking the exercise.

Trust is built incrementally. It’s built over a series of interactions and small steps.

Remember I said earlier that trust is a risk assessment? When you do a risk assessment, you’re looking at your past interactions, and you make a decision. When we interact with people, we get a sense of whether we can trust them, and that all feeds into the risk assessment.

Those interactions can apply to individual people and collective groups.

For example, I’ve been coming to PyCon UK for several years. Everybody I’ve met has always been lovely, charming and nice, so if I come out and meet some of you some first-timers later, I trust I’ll probably have the same experience. I’m judging the group based on interactions with members of the group. [Ed. When Daniele asked “How many people are here for the first time?” in their opening remarks, a lot of hands went up.]

On the other hand, if I said I had a printer in the other room and the printer “just works”, how many of you trust me? (It doesn’t!)

Trust is built incrementally. We have a series of interactions, and as we see trustworthy behavior in a group/person/system, that’s how we know that we’ll be able to trust it in the future.

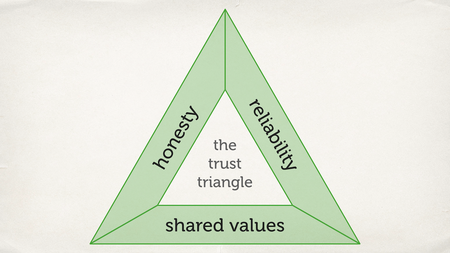

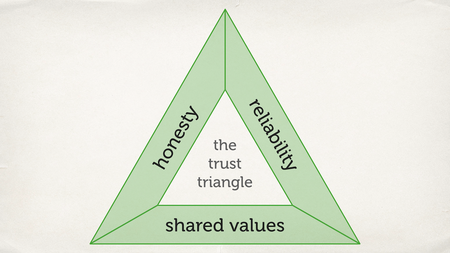

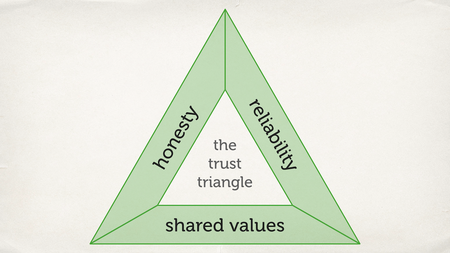

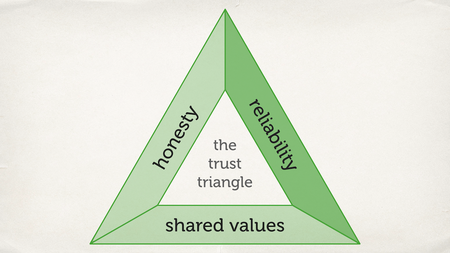

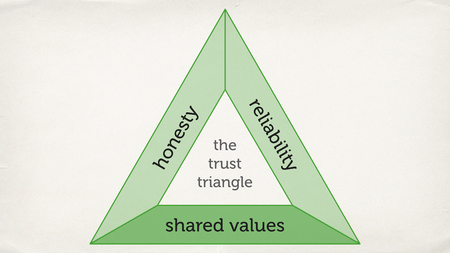

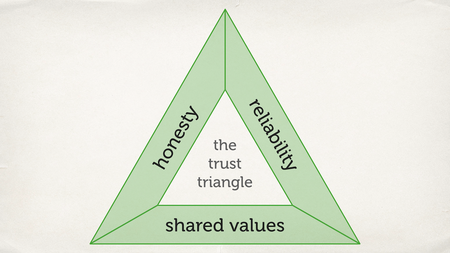

We understand how we build it, so let’s think about how trust works.

Some of you might be familiar with the fire triangle – fuel, heat and oxygen. Wou need all three to make a fire, and if you take one of those things away, you put the fire out.

Trust is very similar. There are three components that you need and you need all three of them. Those components are honesty, reliability and shared values.

Let’s break those down a little.

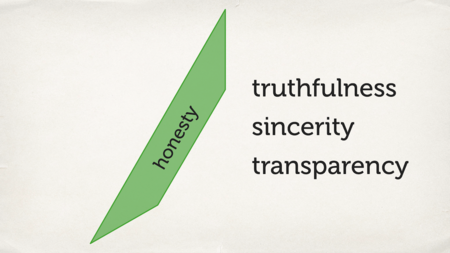

Let’s start with honesty.

For me, honesty encompasses things like:

-

Truthfulness. Do you always say things that are true, or that you believe to be true? Because if you lie to me how can I believe you next time? I won’t believe that you’re telling me the truth.

-

It’s about sincerity – believing that we care about something, that we believe what we’re saying.

-

And finally, transparency. It’s really important to say bad things as well as good things. That doesn’t mean being being mean, but it does mean giving what we’d call an honest opinion.

Imagine, for example, you’ve got a friend who always tells you that you look lovely, no matter what you’re wearing. And then you’re trying out an outfit, maybe because you’re about to go on stage for a big presentation. You ask them, “Do I look okay today?”, and they reply, “Yeah, you look great!”. But they would say that!

So it’s important to be transparent, to say the bad things as well as the good things.

So that’s honesty.

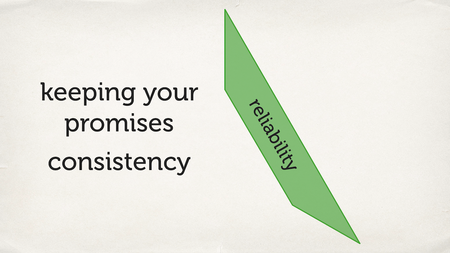

Then we’ve got reliability.

Reliability is about keeping your promises – if you promise you’ll do something, you actually stick to that. You don’t break a promise. You don’t promise more than you can deliver.

It’s also about consistency, and I think in this room we might appreciate that no more than in our test suites. I’m sure many of us have had to debug a flaky test – a test that sometimes passes and then it fails, but you rerun the test and it passes this time. That’s less useful than a test that’s permanently broken, because then you don’t know if you can believe it when it passes again.

Finally, shared values.

This is about things like having common goals. If you’re a team, you’re all going in the same direction. You’re all aiming for the same thing. You’re not heading off in different directions.

It’s having common values and beliefs. You all believe the same thing.

And finally, a common understanding. Raise your hand if you’ve been in a meeting where everybody “agreed” what they were going to do, and everybody had a different idea in their head. [Ed. Quite a few hands went up.] It’s about us all being on the same page.

So those are the things you need for trust – honest, reliability and shared values.

Note that you couldn’t take one of these in isolation and still have trust.

Take honesty, for example. We’d all agree that honesty is a very positive trait. We’d all like to be considered honest people, we’d like to work with honest people, but just because somebody is honest doesn’t mean that you trust them. Imagine somebody who is honest and unreliable – then we believe that they’ll tell the truth, but not that they’ll keep their commitments. The classic example of this is a surgeon who was honest but incompetent – would you trust them to do a major operation on you? (I really hope for your sake that the answer is “no”.)

Those are the ingredients of trust – honesty, reliability and shared values. If you have an environment that encourages and promotes those things, then you have an environment where trust can start to build.

But how do you actually do that?

It’s all very nice to say, “Hey, I want to be a more trustworthy person, so I’m just going to try harder” – but that’s a recipe to get very little done.

We see this when we’re building software. If I want to write less buggy software, I don’t just try harder and magically write better software. I might make small gains, and that’s not nothing, but if we want a step change, we look to external processes – things like tests and code review and documentation. When we want to write better software, we put in place new tools and processes that change the way we work. That enable us to write better software.

Trust is exactly the same – we need new tools and processes – so let’s think about some ways we can do that.

Image: waterfowl ducks, by user 422737 on Pixabay.

Something we can do with trust all by ourselves is being a role model – being something other people can follow. Humans are naturally mimics. We imitate the behavior of the people around us; we see this all the time.

An example: if you’re a company which has one person fudging the financial numbers not, and then management don’t do anything about – other people learn, “Oh, that’s that”, and start to copy them. Eventually it becomes the company culture that it’s fine to cook the books.

So being a role model by showing the behaviors that you want to promote in the world – by being honest, by being reliable, by promoting shared values – that helps other people to do the same.

Image: iPad Air on a brown wooden table, by Burak K on Pexels. CC0.

Another thing you can do that at a high level is having monitoring and check-ins.

There’s no metric for trust – we can’t get a KPI or put it on a dashboard – but it is a thing we have a spidey sense for. When I asked you earlier to think of somebody you didn’t trust, and then somebody you did trust, I think pretty much everyone got it almost immediately – because we do have a sense of how much we trust somebody, and if that trust is declining or increasing.

We can ask if ourselves if we trust somebody – and we can ask them if they trust us. That seems awkward at first, saying suddenly, “Hey, do you trust me?” – but I’ve started doing this a lot in my personal relationships that in the last year – if I’m with a friend and we’ve been seeing each other for a while, I have a quick check in. “Hey, are we good? Is everything okay? Am I being overbearing, is it too much?” That sort of thing.

Actively tracking it helps you see how you’re doing – and when you need to change (and what’s going okay!). Without the monitoring and those check-ins, it’s hard to know what change you need to make, and if it’s having an effect.

So now let’s look at some more specific examples.

I talked about Airbnb earlier. People – your hosts – invite strangers into their home, and one of the things you’d like to ask them on the form is a tickbox “I am not an axe murderer.” “I don’t steal other people’s things.”

But anybody can tick a box on the Internet, so one of the things they do to verify your honesty is ask you for some ID. You upload your government ID, they run that against various databases – are you wanted by the FBI or Interpol, are you a known terrorist? – because if so, maybe people don’t want you in their home.

So that’s an example of a system that actively verifies honesty, and doesn’t just assume on blind faith that people are completely truthful.

Another thing you can think about is incentivizing transparency.

I’m sure we all have managers who tell us they’d love us to be transparent, to tell them when they’re doing something wrong and tell them about their mistakes. That’s a really nice thing to hear, but it’s often difficult to put into practice. If you want to make a complaint at work, and the person at fault is the person who also controls your salary and benefits and career progression, maybe you’ll feel uncomfortable telling them how they screwed up. You’re worried about possible retribution.

It’s one thing saying we want transparency; but to actually do it we have to change the carrot and the stick.

This is an example – I said earlier that I break things. This is a screenshot of our API at work, just before I left for the conference. (I did a production deploy ten minutes before getting on a train, which is always the best time to do production deploys.) It’s not supposed to look like this. Oops.

There was a bug in what I deployed. I could have run out the door and said “I don’t know, didn’t touch it, it must have just broken” – and pretty quickly somebody would have figured it out. They’d look at the logs, see my prod deploy, and 30 seconds later it all goes down, and I’d have been in trouble.

But instead, I fessed up – I said “I broke it”, let’s roll it back, and that was an opportunity for us to have an a discussion about why it broke. How do we stop it breaking next them? There’s a benefit for both the team – to make the API more stable – and there’s benefits for me – because I feel like my coworkers trust me and I know I’m not going to make the same mistake again.

So there’s a benefit to me being transparent, and there’s a penalty for not being transparent. That’s the inverse of the common default.

We changed the incentives of transparency.

Next, let’s talk about reliability.

Going going back to another of the examples from earlier.

Perhaps you wouldn’t feel safe riding in a stranger’s car, but what if you had lots of people who told you “this person is really good at letting strangers ride in that car”? You might be more inclined to do so, and that’s what rating systems do. This is a screenshot from Uber when I came over this morning – but also Amazon, TripAdvisor, Yelp, Google Maps – there are lots of ways we crowdsource ratings.

And those are a measure of reliability. Other people trusted this person, and it worked out okay for them – that’s useful information before we decide to commit.

But what if we’re the person who’s being rated? How do we increase our reliability? A rating is great if you’re already reliable, but how do you get there?

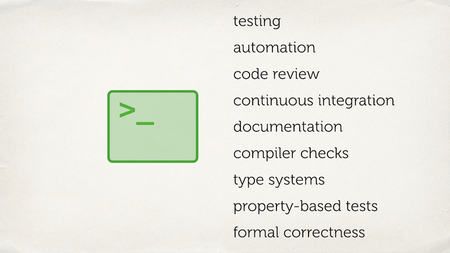

As software developers, we’re pretty good at this, because we’re used to working with unreliable systems – they’re called “computers”.

We build all these different ways to improve the reliability of our software, to improve the reliability of the things we build. Tools like testing and code review and documentation (you all write documentation, right?) and other such things.

We’ve got a huge number systems for improving the quality of the code we write – and something you’ll notice about these is that none of these come from me. These are all external systems.

There’s a Travis server that runs and checks my pull requests pass tests before I merge them. We enforce code reviews through the GitHub UI. The Scala compiler won’t let me write something that doesn’t fit the type system.

We have all these external tools/systems that help us improve our reliability, and we can do the same for the promises we make outside the text editor.

Image: Black and white planner on a grey table, by Bich Tran on Pexels. CC0.

On a personal level, that might be something as simple as keeping a diary or a task list. You can see what promises you’re making so you don’t forget something – so you don’t overpromise and underdeliver – you don’t promise you can do something and not realise that you’ve already promised to do three things this week.

Image: Woman holding yellow post-it note, by rawpixels.com on Pexels. CC0.

Another thing we can look to – if we’re looking at a larger group – is things like agile.

I know to some people that’s a dirty word, but you don’t need to go all in on agile to get some of the benefits. Things like regular stand-up meetings, retrospectives, planning boards – just enough that you all know what you’re doing You all know if you’ve promised to do something, if something is slipping, if a promise isn’t going to be delivered. Again – being really explicit about the tracking and keeping on top of meetings.

There’s a lot of value in some of some of the practices from agile in maintaining reliability in teams.

Finally, let’s think about some shared values.

We most often notice them when they diverge – because shared values are often implicit. We believe that the people around us are inherently reasonable. People hold the same world views as we do, and one day we discover that actually one of the people we work for really isn’t as nice as that. Maybe they hold views we object to, maybe they didn’t undrstand something, maybe they had different beliefs.

The way to get this out is to stop being implicit about shared values – be explicit about them.

One of my favourite lines from the Zen of Python (itself an explicit statement of shared values for Python programmers): explicit is better than implicit.

If we talk about our values and we talk about the things we care about, that can be really valuable. That’s how you close those disagreements.

I asked earlier if any of you had been in meetings where everyone agreed to do something, and they had different ideas of what they’d agreed. So what we often do is have meeting minutes, a list of agreed actions that is sent out to everyone. Something they can look at and say, “Hey I didn’t agree to do that” or “This is different from my memory” but then it comes out in the open – rather than coming back to the next meeting and realising you all thought something different.

One example of a statement of shared values that we’ve already talked about once this morning is the code of conduct. This is an explicit statement of our shared values as organizers, and our beliefs about this event.

If you’re somebody who’s thinking of coming to the conference, you can read this, you can see what our values are and if you thinks this sounds like a friendly conference, then you might come along. And if you read this and it doesn’t align with your worldview; it doesn’t feel like an event where you’d be safe; you might not trust yourself to be okay there – so you don’t come.

By making that explicit and getting it out of the way early, we save ourselves the hassle and time to deal with somebody who turns up with the wrong expectations.

This is a snippet from the code of conduct: PyCon UK will not tolerate harassment.

If you our value of not being harassed at conferences, you can read this and know this is an environment where we don’t want that to happen either. Hopefully that gives you some trust in us that if that happened, we’d take steps to enforce the policy and sanction the harasser.

And indeed if you read the code of conduct, it outlines steps of how we’d enforce these values. It’s not just lip service – we actually follow through on them.

Those are some examples of how you might build external systems and tools, new processes to build trust.

I’m sure you can all think of other ways you might do that in your own life/work/systems.

So we’ve seen how to build trust from scratch – how do you rebuild trust?

What about when it all goes wrong? If you build a trusted system – from honesty, reliability, and shared values – that’s all great, but it’s often very fragile. It’s easy to make a mistake, it all goes wrong, and suddenly you’ve got that loss of trust.

I’m sure we can all imagine a time where we thought we trusted somebody, and it turns out our trust was misplaced. That’s a real gut punch, because while trust is built in small moments, it’s really easy to make one mistake, and trust evaporates instantly. Anybody think of something like that? [Ed. I saw a lot of nodding heads.]

Trust is built incremenentally but destroyed incidentally.

When trust is destroyed, it goes very quickly. A lot of people see this, and then they add a third line, “it’s gone forever”. If you discover you misplaced your trust is something, you never trust it again, I don’t think that’s always true.

Image: Volkswagen grille, from Pxhere. CC0.

Take Volkswagen as an example.

I’m sure many of you may be familiar with the Volkswagen emissions scandal. About two years ago they were caught falsifying their emissions tests. Their engines would pass the EU regulations when tested, then when they sent their cars out on the road, they’d be spewing filthy pollution. This came out, there was big fine, several of their engineers went to prison.

It was a huge loss of trust in VW – a loss of honesty (because they were lying about their tests), and a loss of shared values (in obeying the law and looking after the planet).

But it’s not like VW have now vanished off the face of the earth. People still buy Volkswagen cars. They still own them. They’re still allowed to operate as a business, because there was a huge amount of trust inherent in the brand before they did this this bad thing.

When you lose trust, it’s possible to come back if you have some in reserve and you’re careful about it.

I said earlier that to build trust, you can’t just try harder. In the same way, if you want to rebuild trust or fix a mistake, you can’t just try harder to be more trustworthy in future. It’s important to take explicit steps towards that.

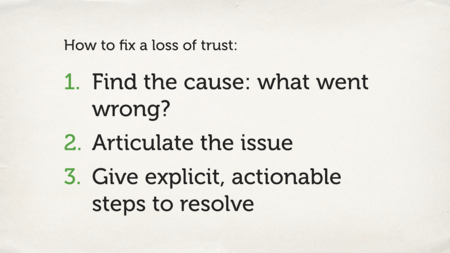

First: find the cause what what went wrong. The first step of making any apology is knowing what you’re apologizing for.

The second is to articulate the issue. I’ve given you a framework today to identify how trust works – again: honesty, reliability, shared values – so what was it? Was it a failure of honesty? Was it a loss of shared values? Was it an unreliable system? Maybe it was all three – but only when you know which component failed do you know what you’ve got to go and fix.

Finally, come up with explicit actionable steps to resolve it. Don’t just try harder next time and hope people will believe you; actually put in place stronger tools and processes to avoid the problem happening again.

Image: British Airways plane against a blue sky, downloaded from Pxhere. CC0.

One industry that does this really well is the aviation industry.

Flying inherently feels a bit weird. We all know how gravity works. We all know that things go down, and planes aren’t going down. Flying should be this incredibly untrustworthy thing, but it’s one of the safest means of transport.

Last year before there were no deaths in commercial aviation. It’s an incredibly safe industry.

Image: Black and white image of a crashed plane, downloaded from Pxhere. CC0.

How did they get there? It’s not like planes never break.

The reason the aviation industry is so trusted and so reliable is because they take a really strong view when there are accidents (or even near misses).

They work through to find out where was the failure of reliability, where was the failure of trust, and how do we rebuild that?

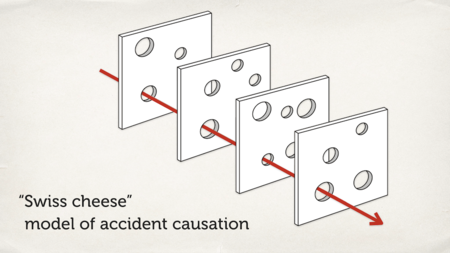

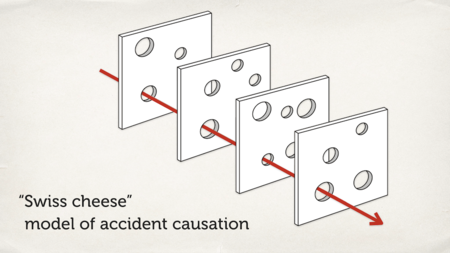

One thing they do that’s really nice is the Swiss cheese model of accident causation.

Some of you may be familiar with this. Imagine every layer of cheese is an overlapping component in your complex system – maybe it’s an aircraft component – and where there’s a hole in the cheese, that’s where a problem can occur. When they line up in just the right way, and there’s a hole all the way through, something can drop through – and that’s when a problem occurs.

When that happens, they try to analyze every layer of the system, every component that could have failed. Find all the bugs and fix them all at once – don’t just fix the last one, don’t just fix the surface problem, fix the reason. Fix all the problems in the system.

Image: Tenerife North Airport, downloaded from Pxhere. CC-BY SA.

One example of that is Tenerife Airport, which in 1977 was the site of the deadliest aviation crash in history. (I’m sorry, I just said aviation is really safe and now I’m telling about a crash!) There were two planes – one of them was taking off, one of them was trying to land. They hit each other side-on, and had a very nasty crash.

How did this happen? The pilot who was taking off thought he’d been given clearance to take off. It turns out the tower thought he hadn’t – so this was a failure of reliability on the pilot promising not to cause accidents, but also a failure shared communication, values, and understanding. The pilot and the tower both thought they knew what “Go for takeoff” meant, and it turns out they both understood completely different things.

It would have been easy for the investigators to say, “Ah, what a silly pilot. They made a mistake and now lots of people are dead. We’d fire them for that mistake, but actually they were killed in the accident, so I guess we’re good now.”

Not only would that be an incredibly insensitive thing to say, it would also not have solved the underlying problem. There were discrepancies in radio communication – and to avoid it happening again, the whole aviation industry now uses really standard phraseology and terminology. They know exactly what it means when somebody says “Cleared for takeoff”. There’s no room for ambiguity. That’s something I think we would often benefit from in the software industry.

One other thing that aviation does which we should steal for the software industry is checklists.

When planes first set off, you had to have a really good memory and remember you’d done all the things to make your plane fly. Have I attached the propeller? Have I put in petrol? Have I taken off the parking brake? Because if you forget any of those things, you won’t go very far.

Eventually, as planes became more and more complex systems it became harder and harder to remember all those things, so they created an external system: a checklist. Now you look at the checklist to tell you everything you need to do to fly a plane.

Taking off? Checklist. Landing? Checklist. Engine failure? Checklist.

And they’re constantly adding new checklists for new scenarios. It gives them a reliable external system for dealing with this complex system.

I think they’d be a useful tool for us to have. Note as well: we’d like to think that as software developers, we’re all really intelligent (and we are!) and that we wouldn’t forget anything (we would!), and so we don’t need checklists. This is a common fallacy.

Another industry that started looking at checklists is healthcare. Now doctors are also really clever people, who you wouldn’t expect to forget things – but every time checklists are introduced, there’s a meaningful and noticeable drop in the rate of accidents and faults in surgery. That’s probably a good thing!

tl;dr: Checklists are great, you should consider using some.

So again: the Swiss cheese model of accident causation. Identifying all layers in a fault, all the reasons why a system went wrong.

Repeat my list of steps for fixing a loss of trust:

- Identify what the issue was

- Articulate how it was a failure of trust; use the framework, use the trust triangle

- Come up with explicit actionable steps to resolve

The funny thing is, when we lose trust, if we rebuild it correctly, we can often end up with more trust than we started with.

Here’s a well-studied phenomenon: If you go into a shop, you buy a piece of clothing, and when you get home the clothes have got a hole in it, the shop has failed in its promise of consistency and reliability. But then you go back and they replace it free of charge – you had a problem, they resolved it. You are more likely to shop there again – even compared to somebody who didn’t have a problem in the first place!

Remember again: trust is built as small interactions. They all build up incrementally, and that’s what gives us the basis to trust somebody. When a mistake happens and you fix it and you fix it well, those are new interactions that feed into somebody’s impression of you; that feed into that layer of trust. A mistake doesn’t have to be the end of the world as long as you don’t let it be.

So let’s recap what I’ve shown you today.

We’ve talked about trust. I’ve shown you my framework for thinking about trust, and how trust is built – honesty, reliability, and shared values. If you encourage all three of those things, you have a system where trust can emerge. If you lose one of them, you have a problem.

I’ve shown you some examples of how you can build new tools, processes and systems to encourage those things – not just to try harder, but come up with ways to verify and validate them.

But if I want to take you to take one thing away from today, it’s this: trust is something you can actively build.

It’s not just a passive thing that happens. It doesn’t have to be something that occurs to you, that you have no control over. You can take actions to affect the trust that other people have in you, and that you have in other people. I’ve shown you my framework for dealing with trust; you might find another system that works better for you. Either way, the important thing is that trust is not just something that happens to you. It is something you can do.

And on that note I’ll finish. Thank you all very much!