Using privilege to improve inclusion

When I go to tech conferences, I’m often drawn to the non-technical talks. Talks about diversity, or management, or culture. So when it came to make a proposal for this year’s PyCon UK, I wanted to see if I could write my own non-technical talk.

Talking about diversity and inclusion can be tricky. It’s easy to be well-intentioned, but end up saying something that’s harmful or offensive. But it’s an important topic — the tech industry has systemic problems with inclusion, and recent news shows us how far we still have to go. I chose it for both those reasons — in part because it’s an important topic, and in part to challenge myself by speaking about a topic I hadn’t tackled before.

This is a talk about privilege. It’s about how we, as people of privilege in the tech industry, can do more to build cultures that are genuinely inclusive.

I first gave this talk at PyCon UK 2017. You can read the slides and notes on this page, or download the slides as a PDF. The notes are a rough approximation of what I planned to say, written after the conference finished. My spoken and written voice are quite different, but it gets the general gist across.

If you’d prefer, you can watch the conference video on YouTube:

A note of thanks

When I was hemming and hawing on the proposal, I got some much-needed encouragement from Samathy, Rae and Chad. Particular thanks to Samathy, who reviewed the initial abstract. Thanks for getting the ball rolling!

I also did a dry run with some friends at work — Alasdair, Alice, David, Gareth, Gemma and Tunde — who all gave me some valuable suggestions, and convinced me the presentation was on the right track.

Thanks to Wellcome for letting me take the time off work, and paying my expenses to I could organise and attend the conference.

And finally, thanks to everyone who came to the talk! Even with the friendly PyCon UK audience, I was quite nervous, but I got a pretty positive reception after I was done.

(Introductory slide)

Image: Tools of the Trade, by Stuart Haygarth. A light installation in the windows of the Wellcome Trust building.

My name is Alex. I’m a software developer at the Wellcome Trust in London, who generously paid for me to attend the conference. If you were at PyCon UK last year [in 2016], you might know that this is a recent change for me — last year’s conference was actually bookended by interviews for this job!

As I was looking at job ads, I noticed a pattern. Companies wanted a GitHub page, a Bitbucket link, a Stack Overflow profile — evidence that I was a “real” developer, that I wrote code in my spare time. And I realised that it tipped the table in favour of people who have the privilege to do work in their off hours, who don’t have other dependents or tasks that need that time.

This is a way my privilege was benefitting me: by making me a more desirable job candidate. And it got me thinking: are there other ways my privilege benefits me? And if so, how can I counter that?

So that’s what we’ll talk about today: how can we, as people of privilege, make our environments more inclusive?

Here “environment” could be a workplace, an open-source project, maybe even a meetup or conference.

I want to provide some practical steps, not just good feelings. And if you’ve come to this talk, you’re probably the sort of person who gets asked about diversity and inclusion — so I want to give you some tools, some phrases you can use the next time you’re asked.

So what do we need to build an inclusive culture?

There are multiple factors, but I think privilege awareness is an important one. It’s necessary, not sufficient (hence the squiggly arrow), and in this talk we’ll see how to turn awareness into action.

First we need to understand the difference between diversity and inclusion. These two terms are often used together, often taken to mean the same thing — but I think there’s an important distinction.

Imagine you’re holding a party.

You want to invite lots of different people — maybe your friends, your family, some people from work — so you write a set of invitations. This is diversity: it’s making sure lots of different people are invited.

When everyone gets to the party, you need to recognise that different people will need different things to feel welcome. Maybe a family member travelled a long way, so you spend time with them so they feel their effort wasn’t wasted. Or a friend has food allergies, so you make sure there’s food available that they can eat. Or a co-worker doesn’t drink alcohol, so you buy soft drinks for them.

You recognise that people are different. You have empathy with your guests. For me, that’s what inclusion is about — recognising people’s differences, and trying to build a place that’s welcoming for everybody.

Diversity is too easily and too often gamed for cheap PR wins; inclusion takes really effort. That’s what we want to do: build environments that are genuinely welcoming.

So now let’s talk about privilege. People often get defensive around that word, and see it as an attack on them if you call them privileged.

People imagine that privilege means having everything handed to you on a plate: being very wealthy, laid-back, with staff on hand. Most of us don’t have this sort of luxury, so we couldn’t be privileged, right?

That’s not what privilege is about.

Link to original tweet: https://twitter.com/jaythenerdkid/status/763451754138701824

This is one of the hardest things about dealing with privilege: this false idea of what it means, so people assume they don’t have it.

Privilege is about having benefits based on traits you possess. For example, I’m a man — I have male privilege — and so people give me the benefit of the doubt. When I go to conferences, it’s assumed that I’m technically competent. I’ve never been asked if I was somebody’s boyfriend (something I’m sure has happened to some of the women in the audience).

More practically, having privilege means there are obstacles you don’t have to deal with. This is the definition I often use.

It doesn’t mean you didn’t work hard, or that your success isn’t guaranteed. It just means that somebody else without your privilege might have to work harder for the same success, because they have different obstacles to you.

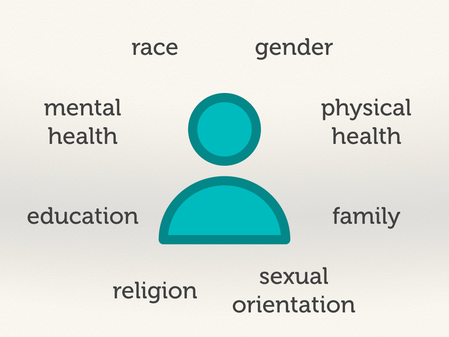

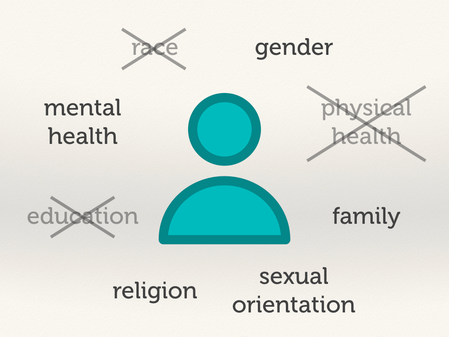

Privilege comes on a number of different axes — there are some examples on this slide.

An exercise: look at the privileges on this slide, and find at least one that you have. Some people in the room will have almost all of them, some people just one or two.

Now, imagine what it would be like if you didn’t have that privilege. How would things be different? How would things be harder?

If you’re white: what would it be like not to have your race privilege? To be a person of colour in tech?

If you have a university degree: imagine you didn’t have your education? Would it be harder to get a job?

If you’re able-bodied: suppose you had difficulty walking, or were in constant pain. How might life change if you lost your physical health privilege?

Hopefully you’re starting to get some idea of the sort of benefits your privilege brings; and the obstacles that people who don’t your privilege will have to face. Now you’ve realised that, how do you do something about it?

Before we go on, one thing: I said at the start that many people feel bad about being told they have privilege. But it’s not bad to have privilege. Indeed, some forms of privilege are chosen before we’re even born (e.g. race, assigned gender). It doesn’t reflect badly on us to have that privilege — it’s what we do with it that matters. In particular, if you ignore the benefits it gives you, you’re deliberately excluding people from your environment.

We’re starting to see how privilege awareness informs inclusion — if we can see where people without our privilege might face obstacles, we can start to reduce or remove them.

Let’s see how to put this into practice.

We want to be an ally for people who have different levels of privilege to us. It’s human nature to bond with people who look like us — people who have the same privilege as us — but it’s much better if we look out for people who are different to us.

And I’ll go one step further: we need to be active allies. Good intentions are all very well, but they don’t change the world. We need to get our hands dirty, actually take action.

The process I’ll explain looks simple when put on slides. It’s harder to put into practice.

The good news: you’ve already started step 1! Introspect and understand your own privilege.

As I said previously, lots of people think they don’t have privilege, and that’s not the case! Think about your own life, background, situation, and understand where you have privilege. This will help you realise your blind spots — what privilege are you taking for granted?

Step 2: listen to people who have different levels of privilege to you, and learn what makes life hard for them. Learn what you can be doing differently to support them.

The thought exercise we did earlier is useful, but it’s hard for us to imagine what it’s actually like. For example, as a cis man, I have no real experience of transphobia — if I notice it, it’s because it’s pretty blatant. I don’t know what it’s like to experience transphobia as a constant, draining, continual shadow cast on my life. If I want to know what that’s like, I have to listen to trans people.

Listening to friends with different levels of privilege will give you ways to be a better ally — maybe things to start doing, causes to support — or things to stop doing. One big change I’ve noticed in the last couple of years is the way I’ve become more careful with words, pausing on language I’ve been told is harmful, which I’d previously use without second thought.

If you don’t have these people in your day-to-day life, social media is great. Find these people, follow them, hear what they have to say.

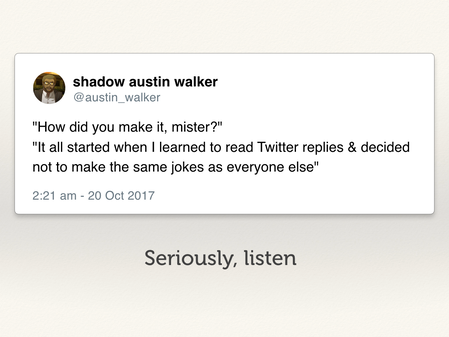

Link to original tweet: https://twitter.com/austin_walker/status/782360503582650368.

Before I move on, let’s emphasise the “listen” part. When they’re getting started, people feel the need to jump in and “correct” people. To explain to them why that’s not actually discrimination, or they’ve misunderstood, or something else.

Don’t be that person.

So once we’ve listened, and found ways to improve, let’s put that into action. Let’s be an active ally.

We can be a voice for people with different levels of privilege. There are a couple of reasons this is important, why we don’t just leave this action to the people who it affects:

-

Marginalised groups often have to do two jobs: the job they’re paid for, and judged by for promotion, salary, advancement — and the job of pushing back against discrimination, fighting stereotypes, being treated as a model for their entire group.

-

They’re not always there! If you’re a man, in a group of only men, and somebody makes a sexist joke, that’s the time to push back. “That’s not okay, and this is why.” Don’t just do it when somebody is around, so you get a cookie.

So let’s look at some examples.

Start with yourself. Are there jokes you make which are harmful, or language which is offensive? Try to avoid saying that stuff.

Then when you’ve started to reduce it in your own language, call out other people. Explain to them why that language could be harmful, and they should use an alternative.

Language is bad, so are stereotypes. If somebody paints with a broad brush, or uses “conventional wisdom”, check to see if it’s really true.

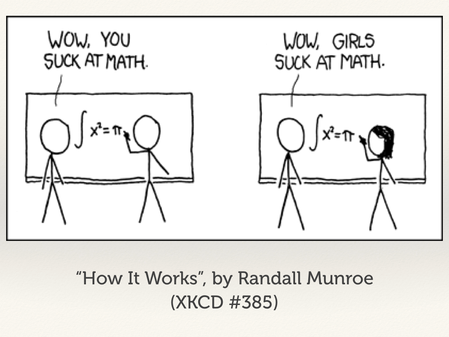

Image: XKCD 385 How It Work, by Randall Munroe.

This XKCD is a particularly famous example. The left-hand character, with no identifying features (who, by the way, we usually assume is male, what does that say about us?) makes a mistake, and is judged badly for it. But when the feminine-coded character on the right-hand side makes the same mistake, it’s seen as an indictment on all women.

This is an unfortunate pattern: people from marginalised groups are treated as representative of the entire group. This puts extra pressure on them not to make mistakes. I’ve seen teams which hire their first woman, she doesn’t gel well with the team, and ends up washing out. This is then seen as evidence that women are just inadequate, rather than a deeper problem with the team itself.

I’ve found a good way to push back on stereotypes is to ask “why”. Do you have evidence, or is it just a hunch? Is there information behind this feeling, or is it just a hunch?

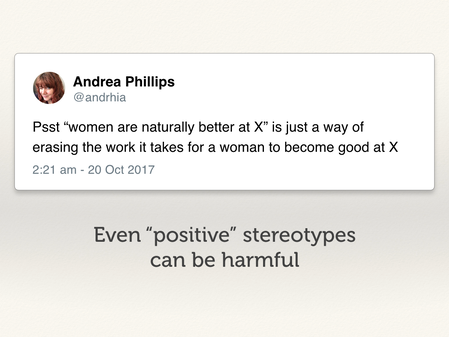

Link to original tweet: https://twitter.com/andrhia/status/921184523693543424.

And even when a stereotype seems like it’s positive, it may still be doing harm to the group.

Finally, we’ve talked about how privilege can be invisible — we don’t see how it helps us. There are similar hidden assumptions in our environments. Look for them: what are their effects? Who might they be keeping out?

An example: it’s now quite common to have daily stand-up meetings. When do you hold your stand-ups? Is that time more convenient for some people? Some companies hold their stand-ups very early in the morning — consider what that might mean for a parent who has to drop off their child at school. What do we think of somebody who always misses stand-up?

But doing this requires subtlety, and there are a few caveats.

First: listening to someone is not the same as having their experience. You can understand the effects, but it’s very difficult to understand what it’s like to live with it. Be careful not to co-opt somebody else’s experience, so present it as if it were your own.

Second: nobody likes to be preached at. You’ve learnt how to be a better ally by empathising with other people — listening to them, learning how the world is different for them. Share that, don’t just tell other people how they should behave better. Share what you’ve learnt, the empathy you’ve gained.

Finally, calling out is powerful. I said earlier that we bond to people who look like us — use that to your advantage.

If somebody gets criticism from a marginalised group, they can write it off. If a woman calls out sexism, they might say “Well, all women are sensitive!” A black person calls out racism: “Black people are too angry!” It’s harder to dismiss criticism that way if it comes from somebody who looks like them.

As a person of privilege, your voice has power, especially among people with the same privilege as you. Use it!

And finally: persevere!

This isn’t a silver bullet. You won’t go to work on Monday, “BAM! Privilege awareness!”, and fix all the problems you have. It’s a slow-moving process of continuous improvement, and it doesn’t fix things overnight. Keep at it, and have faith that if you do it enough, things can get better.

But you’ll get it wrong sometimes. You’ll try to be a good person, and you screw up. Somebody will call you out on it, or you’ll spot it yourself.

Don’t be disheartened, and don’t take it as a sign you should give up. We all make mistakes, and if you apologise and resolve to do better, you can get past it. If you spot you’re making mistakes? That means you’re more aware than you were before!

I think of this stuff as just like any technical skill. You’d never say “I’ve learnt Python, there is nothing more for me to learn”. There’s always more to learn, ways to get better, and it’s continuously changing. Just as a technical skill requires constant improvement and learning — and making mistakes along the way — so does being a welcoming/inclusive environment.

So that’s my four-step process. It looks nice on slides, it can be harder in practice. But I think it’s genuinely worth trying.

If you try this, one of two things will happen. Either, things get better! This is the outcome we want, and it means your environment is becoming more inclusive — and so you keep at it, and continue improving. Or it doesn’t — the culture is too toxic, or stubborn, or stagnant, to change. You tried your best, and nothing changed. Either way, you have more information than you had before, and that can help you decide what you want to do next.

This isn’t easy, but I think it’s worth doing — and slowly we can make the tech industry into the diverse and inclusive place we all want it to be.